In the investing industry, we’re all well aware that our business isn’t a one-person endeavor. The basic problem-solving unit is quite often a group or team. But how do we create the right formula that ensures groups make thoughtful, effective decisions and avoid bad ones?

There’s an old saying that a camel is a horse designed by a committee. This notion points out that groups, even though they have the best of intentions, don’t always make the best decisions. Diversity is a big determinant of success—but diversity for diversity’s sake isn’t enough.

To really make a difference, investment teams must harness diverse perspectives and information while avoiding frictions and costs that can undermine the process. After all, whether the objective is security selection, asset allocation or risk management, the stakes are very high.

Emphasize Diverse Problem-Solving Toolkits

It might be tempting to think that assembling a collection of highly intelligent people from across an organization would provide enough intellectual horsepower to drive very effective investment decisions. But that isn’t necessarily the case.

According to one study1, the intelligence of the smartest person in a group accounted for only 4% of the variance in the group’s performance. Even the group’s average intelligence determined only 9% of its performance variance. In fact, more than 90% of the variance in team performance came from other factors beyond sheer brainpower.

One reason for this result? When many group members—even highly intelligent ones—have similar intellectual “toolkits,” they tend to approach a problem in the same way. That can leave some approaches—and potentially better solutions—out of reach.

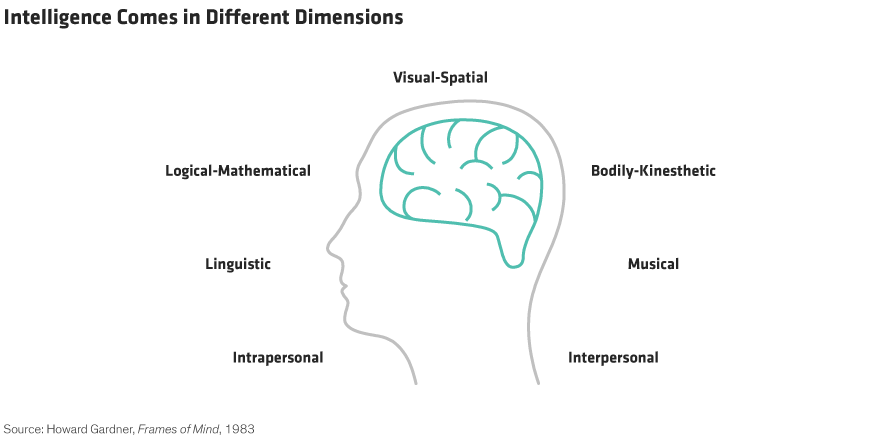

As it turns out, there are other dimensions of intelligence besides cognitive ability alone—including visual-spatial, linguistic and interpersonal intelligence (Display). These different dimensions of intelligence translate into more diverse approaches to problem-solving, which can be a game changer. In other words, diversity of thinking trumps ability.

Ensure Your Efforts Produce Informational Diversity

There have been numerous studies over the years that examined the impact of diversity in group settings. These analyses span many industries, but the collective takeaways can be applied to all types of companies, including financial-services firms.

The assumption is often made that there should be a strong correlation between social-category diversity and informational diversity. It’s true that people of different ethnic backgrounds or genders may well bring a different perspective and way of thinking, but that may not always be the case for every person.

The really important factor, as many studies show, is informational (or cognitive) diversity. Some may use social-category diversity as a proxy for informational diversity: that’s a good start, but it’s important to understand that this is a proxy for what’s really important. If you were to assemble a gender and racially diverse group, but all of them had MBAs from the same school and learned similar approaches to problem-solving, you’re probably not going to get the diversity you think you are. That may be counterintuitive to some people, but what you may actually have built is a group of very similar problem solvers, as we discussed earlier.

Seek Some Common Ground on Values

Value diversity—how people differ in their goals and beliefs—is another key factor in group dynamics. In a problem-solving group, there needs to be some common ground on goals and norms in order for the group to fully leverage its abilities. This is likely why some studies of group diversity show a benefit and some show a negative impact. The differences likely come down to how well diversity is being managed and integrated, which is partly related to values.

The overall takeaway: the goal of team-building should be to assemble the best combination of diverse thinkers from as broad a pool of talent as possible. And diversity can’t be a token effort. Groups must be well managed to avoid internal conflict and friction. Collaboration is the goal—not creative chaos. In the end, the net benefits of diversity equal the gross benefit of individuals’ diverse ways of thinking minus the costs of diversity.

Overcoming Barriers to Effective Groups

Diversity is important, but it’s only half of the solution to running effective groups. Once you’ve assembled a diverse team, it has to be managed carefully to avoid some of the pitfalls of group dynamics. We talk about a “big six” of barriers that can keep groups from functioning optimally. Here they are, along with some advice on how to address them:

1) Too much hierarchy: In overly hierarchical groups, the perspectives and opinions of group members can be drowned out by more powerful members. In many cases, unfortunately, this is how decisions get made. To counter this challenge, it’s critical that firms recognize the challenge of the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion and counter it. One way is to emphasize that leaders should wait to state their opinions until after other group members have weighed in.

2) Hidden information: More talkative group members tend to be viewed as knowing the most, even though that clearly isn’t the case. In one study2 of group decision-making, a hint about the correct answer was given to a group member. When the most talkative member proposed the right answer, 69% of members believed it; when the least talkative member proposed it, only 31% believed it! That’s why it’s critical that every member’s views are heard. Take specific steps to make sure that happens—even if it requires some encouragement of naturally less talkative people.

3) The power of the majority: People in groups tend to conform to the view of the majority—even if that majority is wrong. This is related to human nature, and human nature can be a powerful influence, even for skilled, experienced investment professionals. The only real way for an organization to clear this hurdle is to establish and support a culture that communicates a clear message: if you think differently, you have an obligation to dissent.

4) Group polarization: This challenge is related to the power of the majority. The more groups discuss an issue, the more they tend to gravitate toward extreme positions that can lead to a lack of consensus. Worse, these frictions can spill into other areas of the workplace. Again, organizations need to set clear ground rules showing that opposing viewpoints are always considered. This commitment has to be at the core of an organization in order to empower all employees.

5) Conflict avoidance: A study of the performance of US investment clubs showed that clubs of friends fared much worse than clubs based on professional or financial ties. Friendship-based groups had little conflict, but not because everyone agreed. Instead, they sometimes dodged difficult discussions. As it turns out, some amount of managed conflict is necessary for good group decision-making. Make sure to probe individuals in groups to gauge their conviction and uncover potential agreements based on loyalty or affiliation.

6) Emotional insensitivity: Research has shown that skill in reading other people’s emotions increases the collective intelligence of a group, because it makes the group more sensitive to unspoken issues or areas of disagreement. It’s important to be alert for unexpected body language or verbal queues in group settings—and to follow up on any inconsistencies between verbal and nonverbal communication.

The Big Picture

What does all of this mean for diversity and good decision-making? Clearly, many factors are important to group success. Diversity is a big part of the equation, but how that diversity is managed is critical to generating better, more informed solutions without descending into misalignment and potentially even group chaos.

How much diversity is enough?

It really depends on the type of problem. The more blue-sky the problem—one that requires a highly creative solution with out-of-the-box ideas—the more a wide range of diverse thinking will help. But for narrowly defined tasks, the cost of managing diversity may mean that a smaller group is more effective. The right size and degree of diversity for a corporate board could differ from the optimal structure for a portfolio-management team.

Either way, it’s clear that cognitive diversity—finding, incorporating and properly managing different ways of thinking—can be a key source of competitive advantage.

1Devine, Dennis, and Jennifer Philips, “Do Smarter Teams Do Better?,” Small Group Research (Oct. 2001).

2Henry W. Riecken, “The Effect of Talkativeness on Ability to Influence Group Solutions Problems,” Sociometry, vol. 21, no. 4 (Dec. 1958): 309–311.

Stuart Rae is Chief Investment Officer—Asia-Pacific Value Equities

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.