This is a part of our “COVID as a Catalyst” series. You can read the introduction to the series here. The first topic, “The End of the Era of Good Macro?” is available here. The second topic, “A Tailwind for Technological Adoption,” is available here. The third topic, “Will Efficiency Fall by the Wayside in a Riskier World?” is available here.

When a public health crisis spirals into an economic crisis, it casts a light on many areas of society at once. The coronavirus pandemic has shined that light on cracks in the American social contract and social safety net.

First, it is testing the modern US healthcare system and social safety net in ways that they’ve never been tested since their emergence out of the New Deal and Great Society movements. Second, the pandemic has exposed critical divisions in our society—while some people have had no problem adapting and staying safe, others have been forced to bear much more risk. Those divisions have fallen not only along socioeconomic but also racial lines, capturing the nation’s attention in a new way.

SAFEGUARDING THE SAFETY NET

The US healthcare system has two characteristics that have been at the center of debate for years and create additional challenges in the face of a pandemic-induced recession.

Our system is geared toward individuals rather than the total population. At the early stages of the outbreak, that meant that an uninsured or underinsured person may not have sought virus testing and/or medical assistance due to the cost, which then allowed the disease to go undiagnosed and untreated. This likely led to that person infecting others. That is far from optimal for society overall, as the misaligned incentives allowed for further community spread and made the coronavirus even harder to contain.

Further exacerbating the issue, the majority of the US population under 65 years old receives health insurance through their employer, which works when times are good, but becomes a major problem during a downturn when people begin losing their jobs. And that problem is magnified when the downturn is caused by an ongoing public health crisis.

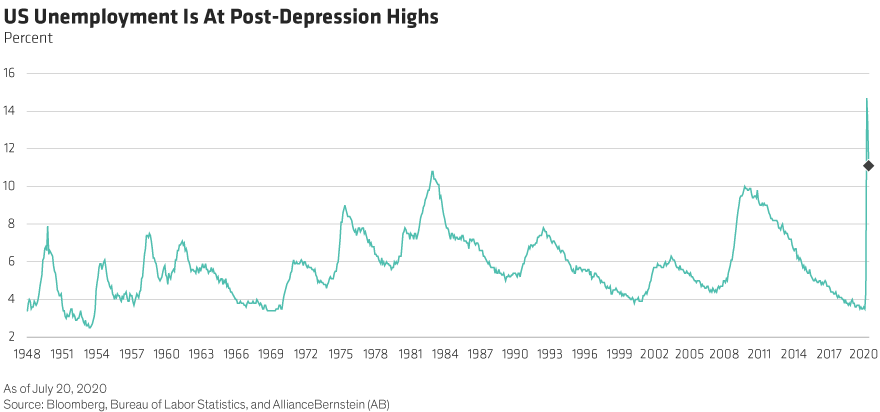

In the first week of statewide lockdowns alone, over three million workers lost their jobs, dwarfing the previous record of 670,000 losses. From mid-March through mid-July, over 52 million people filed initial unemployment claims. To put that in context, that’s roughly 1 in every 3 people who were employed in February. Even as the incremental job losses have decreased over the course of the pandemic, last week’s jobless claims would be almost twice the pre-pandemic record on their own. Thankfully, many workers have been able to return to their jobs, leaving the unemployment rate around 11%.1 Yet that’s still higher than it’s been during any recession since the Great Depression.

All of these job losses are occurring at a time when health insurance is more vital than ever. There is no doubt that health insurance, its links to employers, and its ability to respond to pandemics or other emergencies will be a major political issue in the wake of the crisis.

Aside from the burden the virus is putting on our nation’s hospitals, our unemployment system is also being challenged. Our economic resources and the impact of the virus span the nation. Yet the unemployment system is administered by states. People who have recently moved to a new state may fall between the cracks in the system. In addition, the requirements and benefits may vary from state to state, making it that much harder to coordinate a nationwide response. Finally, the severity of the recession is rapidly depleting states’ unemployment funds, forcing them to turn to Washington for help.

The federal government has attempted to fill these gaps by supporting reimbursement for coronavirus testing, bolstering unemployment insurance for those who can get it, and sending checks to lower- and middle-class families around the country. On the other hand, while the states that administer their own insurance exchanges and the District of Columbia have reopened their insurance enrollment, the White House has refused to grant federal approval for the states that rely on the Healthcare.gov portal to do the same. As the conservative American Enterprise Institute has written, that refusal will “needlessly make matters worse for millions of Americans who lose both their jobs and their health insurance” and “will make the public health problem worse.” While the government is now offering to pay for coronavirus testing and treatment for the uninsured, clerical issues and billing confusion have still occurred. And that coverage of pandemic testing and treatment does nothing to help people who lose their employer-provided health insurance and need to pay substantial sums out of pocket for health insurance or non-covid medical procedures.

When the crisis has subsided, we expect an uptick in the debate around the social safety net—whether an overhaul is needed or whether ad hoc measures like those being implemented right now suffice. It’s possible nothing will change, but we expect policies will be implemented to bolster the healthcare system and moderate the impact of future recessions on individuals. One side of that debate was recently staked out by a group of Democrats and would include implementing automatic stabilizers in the system. The Republicans have yet to counter with their post-pandemic healthcare vision, but there’s sure to be contentious debate regardless of how the November elections turn out.

Depending on that debate and the outcome of the election, the actions taken would affect the magnitude of future downturns and redirect some of the cash flows in the healthcare sector. If additional measures are implemented, that could reduce the risk and volatility in the economy as well as provide more of a safety net for entrepreneurs delivering innovation and growth. If government programs expand, health companies geared to that type of business should benefit. At the same time, if government involvement increases, it would likely have a negative impact on the prices of drugs and other healthcare products and services. From a macroeconomic perspective, it would also need to be paid for in some way.

ONE PANDEMIC, UNEQUAL IMPACTS

The pandemic has also exacerbated other political divides. It has laid bare the differences in our society along educational, socioeconomic, and most jarringly, racial lines. These divides can be seen in the digitally rich and the digitally poor, the employed and the unemployed, the healthy and the sick.

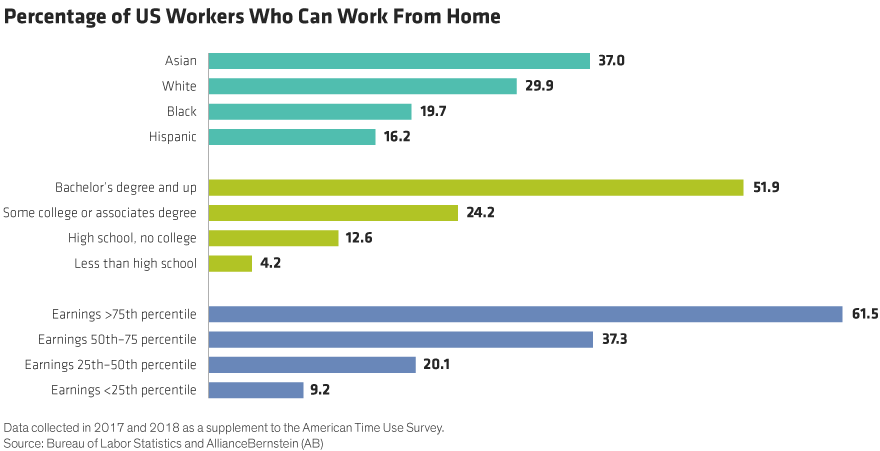

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 37% of Asian Americans and 30% of White Americans say they can work from home while the figures for African Americans and Hispanics are only 20% and 16%, respectively. The education divide is more stark, with over half of people with a bachelor’s degree or higher able to work remotely while only 12% of those who only completed high school and 4% of those with less than a high school diploma can. And by income, it’s even more stark—62% of workers with top-quartile incomes can work from home while only 9% of those with bottom-quartile incomes can.

This pandemic has inflamed tensions along each of these divides. It’s fostered resentment from workers forced to take personal health risks in order to pay their rent or put food on their table. Those forced to venture out to work, those with less medical care, and those with less money have been struck harder by the virus than the rest of society.

According to NPR and the COVID Racial Tracker, nationally, African American deaths outpace their share of the population by a factor of two. In four states, their death rate is three or more times greater than their population share. Likewise, in 42 states and the District of Columbia, people of Hispanic backgrounds are dying at a disproportionate rate, and in eight states, the rate is more than four times greater.

The impact on businesses has also unfolded along racial lines, according to a study by University of California—Santa Cruz professor Robert Fairlie, with the fall in activity most severe for African American business owners, then Latinos, then Asian Americans, and finally for White Americans.

All of this is likely to affect our politics and, ultimately, economic policy. When voters turn out at the polls this fall and in the coming years, politicians who ignore that unequal burden are likely to face costs of their own. Politicians who offer real solutions are likely to be rewarded.

If the government can implement policies that create better education opportunities, allow financing to flow more freely to entrepreneurs, improve people’s health, and dampen the shocks of life regardless of one’s race, that should enhance the nation’s well-being, societal cohesion, and last but certainly not least, economic prosperity.

INVESTING FOR THE ROAD AHEAD

The current times are trying, but we are by our nature optimists who hope to see the world, the economy, and people’s lives improve over time. And we believe that will happen through this pandemic, albeit slowly.

As we work to get to the other side of this pandemic and eventually emerge from it, the lessons we’ve learned and the scars we’ve endured along the way will likely shape our politics, our policies, our economy, and our lives for years to come. It will affect the balance between labor and capital. It will affect the social safety net. It will affect the access we all have to resources and opportunities.

In turn, those impacts will drive where we as investors see headwinds and tailwinds for corporate revenues and the extent to which future shocks impact the economy. Over time, economic progress leads directly to the returns of risk assets, including stocks and bonds. By owning these assets, investors participate in that development and growth over the long term. With a portfolio diversified across geographies, asset classes, and industries, they can capture the benefits of that progress while minimizing the risks from any specific event.

1Due to measurement difficulties surrounding business surveys during the pandemic, mainstream economists estimate the real unemployment rate is around 13%. In addition, the figure would be closer to 20% if not for 5 million people who were employed in February but are now not working and not actively looking for work—they do not count as part of the labor force or the headline unemployment figure.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.