Just over one year since Amazon acquired Whole Foods, the grocery industry is still figuring out what the future of food retail will look like. This $5 trillion global industry has always been competitive—grocery stores have fought each other for market share while sporting razor-thin profit margins. But external pressures from other retail channels—club stores, supercenters, dollar stores, drugstores, and now e-commerce—are forcing many grocers to reevaluate their strategies.

The tired format of browsing aisle by aisle is being replaced by new models—click and deliver, click and collect, and meal kits. But adapting store formats is not easy—it takes a large investment, particularly in IT infrastructure. Unfortunately, it is uneconomical to convert many store locations to new formats because many have massive square feet of legacy real estate. These grocers are laden with high debt and cannot afford to upgrade. Others don’t have the physical scale to make widespread distribution networks feasible for the new paradigm. This spells doom for many, and opportunity for a few.

A Stampede Afoot?

The US grocery industry is highly fragmented; nearly 60% of the 36,500 US grocers are independent. The industry also has relatively low concentration; the top four companies control less than 45% of the market, while the 21,000 independent grocers comprise 25% of total industry sales.

Independent grocers face multiple challenges. Because they lack scale, they cannot operate at low costs, effectively develop private-label brands, or own their entire grocery supply chains. Additionally, they have less capital available for new initiatives. As competitive pressures grow, independents will be disadvantaged whereas larger grocery chains can improve their cost structures through pressure on suppliers and process improvements, and absorb lower prices. Most small grocers cannot.

Being Outgunned

This year alone, two grocery chains, Tops Markets and Southern Grocers, owners of Winn-Dixie, Harvey’s, and Bi-Lo stores, declared bankruptcy. While bankruptcies and mergers are not uncommon in the grocery space, today fiercer competition is forcing weaker chains out even quicker. Competitive pressures are adding to an already low-growth environment; over the last five years, the grocery industry averaged only 2% growth, and we don’t expect future industry growth rates to change meaningfully.

Part of the problem is the ownership structure, which has put a lid on a grocer’s ability to reinvest to adapt and grow. Many grocery chains are owned by private equity, which piled on tremendous debt to their corporate structures. In Tops’ bankruptcy filing, it commented that it could neither afford to offer organic, premium products its high-end competitors are pushing, nor make price cuts that would attract a value shopper because it is saddled with high interest payments on its debt. They are not alone.

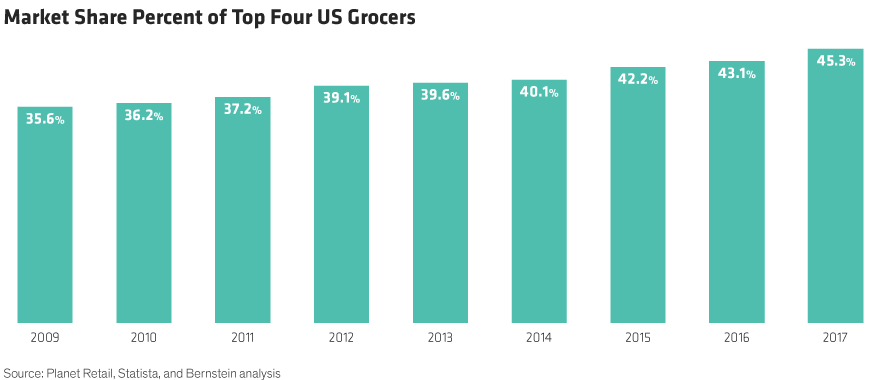

The industry has been consolidating for many years and we believe the pace of consolidation will likely increase (Display).

As a result, the largest US grocers will grow larger as market share comes up for grabs as smaller independents go under. This will enhance the large chains’ ability to compete by increasing scale advantages of buying power and fulfillment costs. Even with competition from new entrants like Amazon, or deep discount chains, the large grocers should have enough scale and built-in advantages, like experience with grocery supply chains, to ward off competition. We believe the total share loss for large grocers will be very minimal in the face of intense competition.

Historically, margins increase by 150 basis points as markets move from fragmented to concentrated.* The large grocers who can take advantage of failing smaller players, and grow market share, should benefit with higher margins over time even as changing shopping habits siphon off customers to new competitors.

New Entrants Change Old Habits

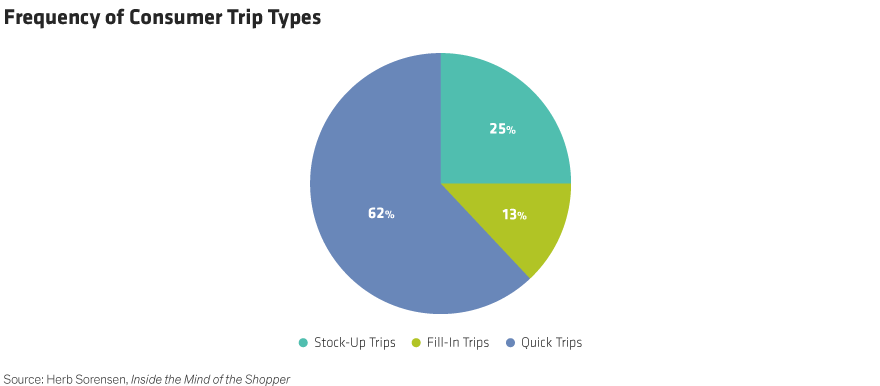

The competitive threat to incumbent grocers is coming from new entrants and the changing habits of shoppers. Consumers make distinct types of shopping trips—stock-up, fill-in, or quick trips (Display). Around 40% of shopping trips are for stock-up and fill-in where larger grocers have the advantage, whereas many of the new competitors—the convenience, drug, and dollar stores—satisfy quick trips. Quick trips to buy core essential products like eggs and milk, have heavy price competition and thus low margins. So, the total profit hit to large grocers, like Walmart, from the loss of quick-trip customers will be relatively small. Smaller and independent grocers, however, will be affected and may be forced to close or merge with another retailer.

The impact of e-commerce is harder to determine. Shoppers accustomed to packages showing up on their doorstep within a few days (or a few hours!) have set the bar high for incumbents and new entrants alike. Meeting these expectations will be much more challenging when the items being delivered are food. That’s because food is much bulkier and heavier than non-food products and requires specialized logistics to keep items cold and fresh, all of which adds costs and may require additional fees to make it feasible. Grocers with large, existing local store networks have a distinct advantage over other companies, like Amazon, because the cost to deliver the last mile is high. We think this was one of the primary motivations for Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods, to acquire an existing network of physical store locations from which to build a national platform.

Online ordering isn’t limited just to home delivery. Given the costs and logistical challenges of delivering bulky, low-margin food items direct to customers, grocery chains will continue to invest in click and collect formats whereby shoppers place their orders online and then drive to a nearby location to pick up their items. Just as with home delivery, click and collect formats require physical infrastructure and grant an advantage to grocers with established locations. As a result, the impact of an Amazon or other national e-commerce threat will be relatively muted for now. But online food ordering is expected to continue to grow and large grocers need to invest to improve their digital platforms.

A Technological Revolution

Amazon’s entry into the industry was a wake-up call for many companies that were slow to recognize or adapt to the changing habits and behaviors of consumers. Larger, national chains need to identify the importance of technology to grow market share. Kroger, for example, recently struck a deal with UK online grocer, Ocado, to build a credible e-commerce platform. Walmart is also investing heavily in technology.

IT investment is necessary to stay ahead, for many reasons. First, technology can aid in food safety—the growing need and demand for safe and traceable food. Second, it will help reduce costs and improve efficiency to remain competitive on prices. Lastly, it will target consumer preferences and entice new and repeat business. Consumer preferences include customized advertisements based on past purchasing behavior or creating a platform that caters to click and collect or delivery preferences.

The Future Is Now

Although there are numerous threats to the grocery industry, the largest grocers should be able to ward them off, while benefiting from the expected wave of consolidation. As with any highly competitive industry, those companies that can leverage scale and increase operating efficiencies should be best positioned to gain share. But today, there’s a new wrinkle—online food ordering—that requires companies to make investments in technology. Although delivery costs are prohibitive for many today, other formats may prove more feasible, but still require investment. Click and collect, for example, is a growing trend that requires the reallocation of physical space in addition to a technology platform to succeed. This is the future, and those companies that recognize these changes and adapt will be the eventual winners.

To learn more, listen to our podcast, Getting the Dish on the Grocery Market.

*Source: Capital IQ, Bloomberg, Company reports, AB

An information edge can mean the difference between getting ahead—or being left behind. That’s why many of our entrepreneurial clients look to us as a source of intellectual capital. For more insights on disruption, check out the related blogs here.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice, or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.