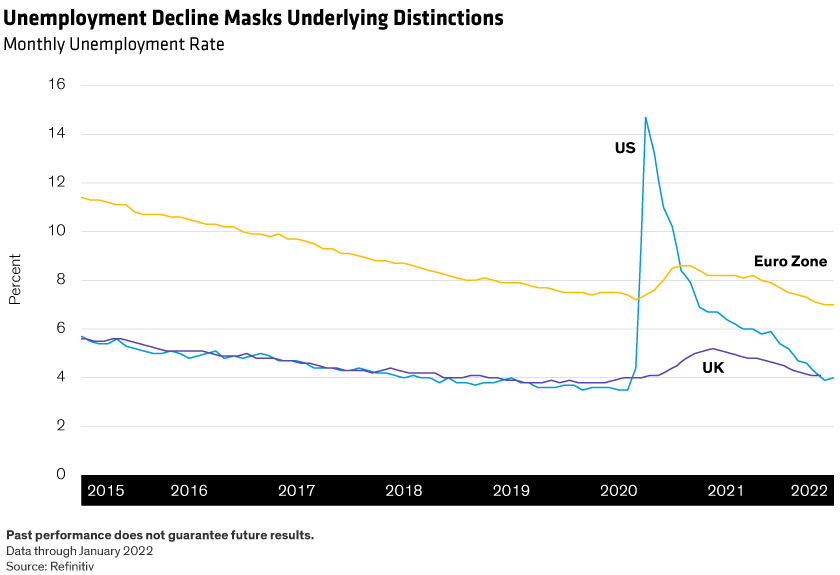

At first glance, most of the developed world seems to be enjoying a synchronized labor market recovery as COVID-19 fades. Unemployment rates in the major economies have fallen back to, and in some cases below, pre-crisis levels as businesses have reopened and consumer demand risen (Display).

But that apparent similarity masks a critical difference. Because the unemployment rate is calculated using only people who are available to work, it presents an incomplete picture. Under the surface, the US experience stands out as a clear exception: despite the falling unemployment rate, the number of people working in the US today is still below the pre-crisis level (Display).

Where have all the workers gone, and why does the US experience stand out from the crowd? It’s a critical question for future growth prospects, because the potential growth of gross domestic product (GDP) is defined in large part by the number of workers available. If that number is down permanently, future GDP is likely to be lower than hoped.

The Great Resignation in the US

On the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 155 million people were employed in the US. Wages were rising gradually, but reports of worker shortages were scarce, and few people would have described the US labor market or economy as overheating.

A scant two years later, 152 million people are employed—three million fewer than pre-pandemic. Wages are rising sharply, and worker shortages dominate any discussion of the labor market. Many had expected that the expiration of enhanced unemployment benefits would prod millions of workers to rejoin the labor market, but that didn’t happen. In contrast, workers in the UK and in Europe have returned to the factory or the office in greater numbers than before the crisis.

Fiscal Support Is a Key Distinction

Part of the difference stems from the nature of fiscal support. The US government provides benefits directly to workers who lose their jobs, which allows businesses to shed employees rapidly during a recession. Europe operates much differently: it has prioritized employment stability, providing support to workers through their employers, alleviating much of the need for firms to shed staff.

The distinction was clearly seen in the impact on employment in the early stages of the pandemic. The US shed nearly 15 percent of its workforce, about five times more than the euro area or UK. Of course, it’s a lot easier for employees to return to a job they had before than to find a new one, which likely explains part of the US labor force’s failure to get back to its starting point. But we think there’s much more to it than that.

Demographics: Retirement Timing and Means

The most obvious reason for lower labor force participation is the aging Baby Boomer generation, which has driven a long-term decline in the participation rate for the past two decades. The trend paused in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC), with older workers delaying retirement given the strong labor market and lingering concerns about financial stability. These dynamics kept the labor participation rate largely stable from 2012–2020.

But demographics are inevitable—retirement delayed isn’t the same as retirement avoided. The US population of those 65 year and older is growing by roughly 1.5 million per year, and the COVID-19 experience has induced many of those who stayed in the workforce even as they aged to leave it now. Older people are more vulnerable to COVID-19, so it makes sense that fewer would be eager to continue working in a riskier environment.

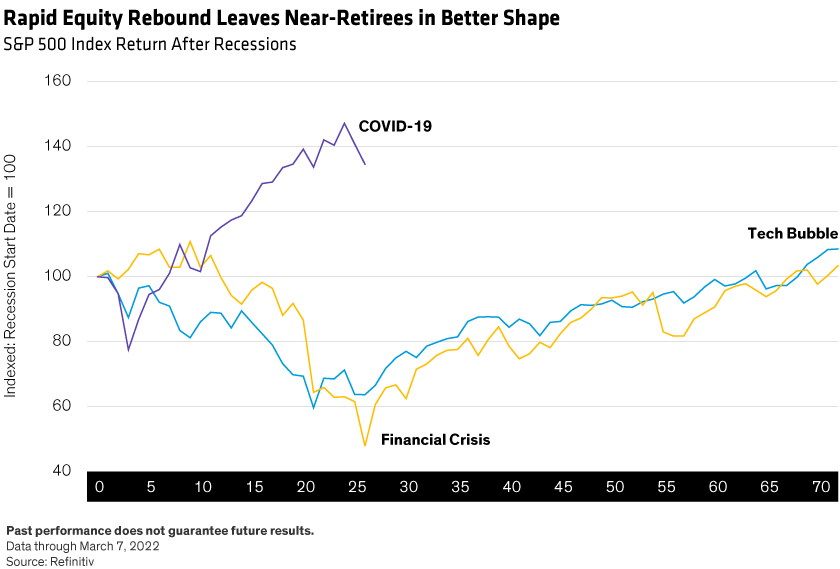

Strong capital markets and household finances in recent years mean that fewer potential retirees face financial pressure to stay in the workforce—a dramatic change from past recessions (Display). Most recently, the S&P 500 took several years to regain its prior peak after the GFC, and many workers on the cusp of retirement found that their eroded savings gave them little choice but to keep working.

After the COVID-19-related sell-off, by contrast, the equity market made up its lost ground within a few months and has risen even further since. That rebound leaves people on the cusp of retirement before the pandemic in much better shape financially today. Assets have outgrown income dramatically, making earned income less important for later-career workers. Add that to the greater health risks of working, and the decision to retire doesn’t seem that hard to make.

Changing immigration flows are another demographic factor driving labor shortages. Net immigration to the US peaked in 2016, fell pre-COVID-19 as the social and political climate changed, then collapsed during the pandemic. Based on most estimates, about half of all immigrants find their way into the labor force, so the shortfall of two million immigrants since 2016 translates into roughly a million fewer workers.

Lingering Pandemic Effects…and a Reassessment of Work Preferences

But demographics don’t fully explain all of the missing workers. Even among prime-age workers, the participation rate is below pre-pandemic levels. Part of the issue likely stems from lingering pandemic effects.

Unpredictable and unreliable childcare has been a particular impediment to women rejoining the labor force, bringing a screeching halt to one of the biggest successes of the pre-pandemic economy. The participation rate for prime-age females (25–54 years old) plummeted during the crisis and has yet to regain the pre-pandemic level, though recent signs are encouraging.

More broadly, workers seem to be reassessing the conditions and compensation they’re willing to accept to take a job. From a long-term perspective, this shouldn’t come as a surprise; if anything, the better question may be why it took workers so long.

The dramatic decline of organized labor’s role in the US economy—from more than 30% of workers in unions through the 1970s to roughly 10% today—enabled employers to more or less dictate terms. Not surprisingly, the gap between corporate profits and the household paycheck has been widening steadily as workers have lost the ability to organize collectively.

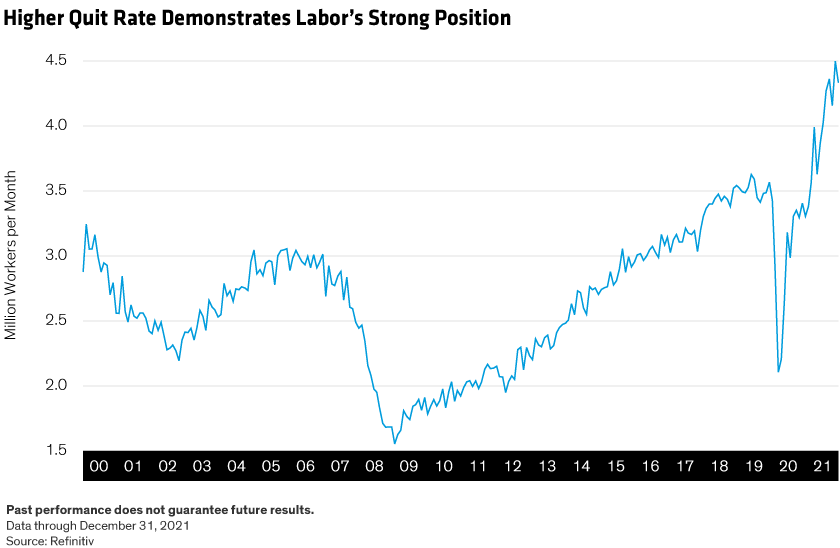

Profits accelerated further in the aftermath of COVID-19, driving the gap to unseen levels—just as demographics reduced the pool of readily available workers. This flipped negotiating power from employers to workers, who’ve been quick to recognize the opportunity to capture a larger share of national income. They’re in demand and businesses can pay them more.

We can see the altered power dynamic by looking at the rising “quit rate”—the number of workers in any given month who voluntarily leave their jobs (Display). Most workers don’t leave unless they have a better job to go to, making this metric a particularly good measure of both the strength of the labor market and the balance of power between employers and employees.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Because no single variable is responsible for the tight labor market, the path forward remains murky.

Some parts of the current environment will likely persist: older workers won’t get younger and most people who’ve retired are likely to stay retired, for example. Other issues may resolve more quickly. The political climate may preclude immigration flows from returning to prior levels, but some rebound is likely as COVID-19 impediments fade. Similarly, if the public-health situation continues to improve, more reliable childcare should enable more workers, and more women especially, to rejoin the labor force.

That said, post-pandemic labor participation will probably remain below pre-pandemic levels, making employers work harder to hire and keep workers. Higher wages are the easiest path, so we expect upward wage pressures to remain, though perhaps below current levels as the economy normalizes. Workers may have the upper hand for now, but the next economic downturn that compels businesses to reduce staff could again alter the balance dramatically, given the low union participation.

Until then, many workers who’ve left the labor force likely aren’t coming back. Fewer workers means more wage pressures and more inflation earlier in the cycle than policymakers would prefer—or expected before the pandemic arrived. The heat will be on the Fed and other central banks around the world to raise rates earlier, even if it means slowing growth.

Eric Winograd is Director of Developed Market Research at AllianceBernstein (AB).

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations, and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.