By the summer of 2020, the world was six months into the COVID-19 pandemic. The first wave alone is more expansive—and global—than other 21st-century outbreaks, including severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome and even Ebola.

The economic impact of COVID-19 is already historic. To control spread of the virus, governments brought a sudden halt to economic activity with social distancing restrictions and shutdowns, causing massive labor-market dislocations. The scale of the public-health, monetary and fiscal response is simply unprecedented.

If these actions are successful, restrictions will eventually be lifted and economies should recover. But what happens after the initial bounce? Prior to the pandemic’s outbreak, we sketched out five long-term trends that we believe will drive an environment of weak growth, a deteriorating growth-inflation mix and, ultimately, a shift to higher inflation itself:

- A negative supply shock from demographics

- Weak productivity growth

- Resurging populist policies

- Rising geopolitical competition and conflict

- A mounting debt overhang

Will COVID-19 reinforce these trends, counter them or have no effect? The pandemic has already ushered in major changes. For consumers, movies and airline travel are now off the menu, while for producers, densely packed workspaces are a thing of the past. Failed and bankrupted businesses and financial-sector impairment from collapsing asset prices and bad debt will not be uncommon. And even as restrictions are gradually eased, it may be a long time before people feel safe returning to “normal” behavior.

But the pandemic’s easiest path to influence long-term macro outcomes is where it’s pushing in the same direction as long-term trends that are already under way. Think of this as pushing on an open door.

COVID-19 WILL LIKELY INTENSIFY DEGLOBALIZATION

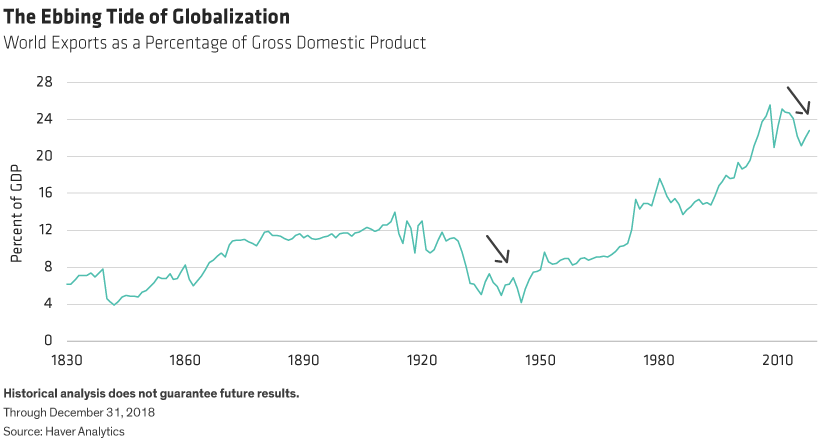

Globalization is one of those open doors, given its apparent peak before the pandemic arrived. A simple way to visualize the globalization trend is by looking at the ratio of exports to gross domestic product (GDP). This ratio rose steadily as globalization made headway in the decades after World War II. More globalization meant more goods and services shipped outside national borders.

Since 2013, though, this trend has started to reverse (Display 1), partly because the global financial crisis (GFC) revealed flaws in global supply chains—notably the reliance on trade financing. Technology—automation, in particular—is pushing on the open door, too, by making onshoring production a viable option versus offshoring to low-wage-labor nations. And, of course, the institutional framework for free trade has been shaken by trade wars, due in part to a resurgence in populism.

COVID-19 arguably pushes the open door for deglobalization even further, revealing more supply-chain flaws concentrated around single points of failure. Regions of the world that had been more globally connected or networked have felt a deeper impact. But this isn’t just about supply chains; indeed, escalating geopolitical conflict between China and the West in the wake of COVID-19 threatens to push the deglobalization door wide open.