Around the world, interest rates are at the lowest levels in human history. Given how important they are for everything from mortgages to stock portfolios, that’s got a lot of people concerned.

With $13.5 trillion in bonds worldwide offering negative yields to investors, the controversy is intense. Are we in the greatest bubble of all time? Have central bankers gone too far? Or is there a more mundane explanation?

And of course, everyone wants to know—what will happen next?

After careful analysis, we believe that today’s low yields are not the result of a bubble, conspiracy, or market manipulation. Rather, as detailed in our latest white paper, they’re likely the result of a multi-decade trend in US and global demographics, of growing income inequality and monopoly power, and of people saving more as a response to lower rates themselves.

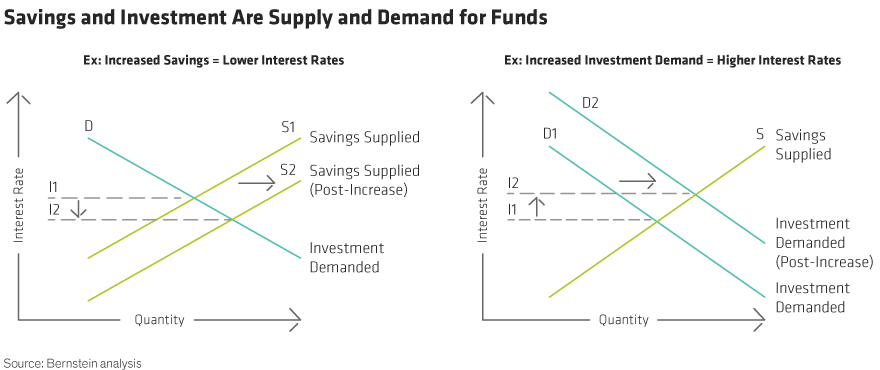

Interest rates are, at their simplest, the (rental) price of money. And the price of money, like the price of any commodity, is the result of supply and demand. Only in the case of money, economists call the supply of funds “savings” and the demand for funds “investment.” Interest rates connect savers (who supply funds) with investors (who borrow funds in order to pursue productive projects). Increases in savings increase supply and lower interest rates, while increases in investment have the opposite effect (Display 1).

As a result, the fall in real (ex-inflation) interest rates in the past four decades can be understood as the result of savings overpowering investment. But why did that happen? There’s been a confluence of factors.

The growing budget deficit over time, for one, decreased national savings. But that effect was more than overwhelmed by increases in savings and decreases in the demand for funds elsewhere.

US DEMOGRAPHICS

Under the broad term “demographics” are a few key drivers, each of which has a different effect on interest rates. Of all the drivers that structurally influence rates, demographics are the most interesting today because several longstanding trends are stalling or reversing.

Life expectancy—In general, as life expectancies rise, people choose to save more throughout their working lives to fund longer retirements. Those higher savings rates pressure interest rates lower. As life expectancies have risen in recent decades, they’ve pushed rates down.

Fertility—Falling fertility rates work differently but have also pushed rates lower. Lower fertility rates increase the capital-to-labor ratio in an economy, which makes incremental capital less valuable and in turn lowers the demand for funds, and with it, interest rates.

Population growth—Changes in life expectancy and fertility (along with immigration) lead to changes in the population growth rate. Population growth in the US has been slowing since the 1950s. This has two effects:

- Initially, like lower fertility rates, it reduces the value of incremental capital and pushes interest rates down.

- But over a longer horizon, it increases the proportion of retirees in the population. Since retirees spend money out of savings, this larger pool of retirees drives down national savings and drives up interest rates.

Length of working life and length of retirement—In the US and other developed countries, retirement ages fell steadily in the decades following 1970 and retirement lengths nearly doubled. That meant people needed to save more during each of their working years and/or spend less in each of their retirement years, pushing up savings and pushing down rates.

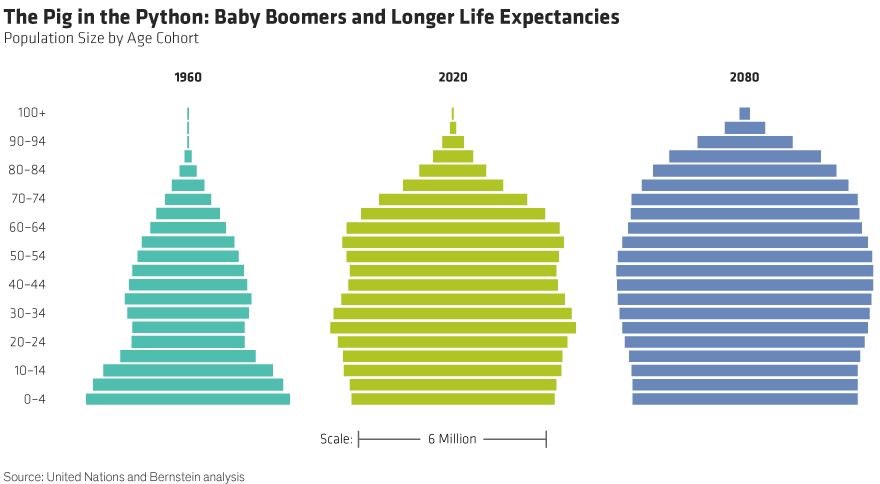

Employment-to-population ratio—Since workers save and retirees spend, a higher proportion of workers in the economy translates into a higher national savings rate and pushes interest rates down. This is the demographic dividend the baby boomer generation provided over the past several decades. But remember the lagged effect of declining population growth—as more of the population ages, the effect reverses and those retirees put upward pressure on rates (Display 2).

INTERNATIONAL DEMOGRAPHICS AND GLOBAL GROWTH

US assets and interest rates don’t exist in a vacuum. Global drivers are also critical. Demographic trends in the developed world have paralleled those in the US. The demand for Treasuries from Japan, China, and other countries has led to what former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke described as a “savings glut.” This too has weighed on interest rates in the US and overseas.

INCOME INEQUALITY

Inequality is one of the pivotal issues of our current age. It has economic effects, but even more importantly, it has political consequences.

Since the rich are more likely to save an incremental dollar of income, as incomes have skewed more toward them, it’s put upward pressure on savings and downward pressure on rates. That is further exacerbated by the fact that the rich, by definition, have more money. So their higher savings rate is applied to a larger dollar value, giving it a disproportionate impact on national savings.

MARKET POWER

Increased industry concentration and the rise of oligopolies have also lowered rates. Because a company with more market power can grow faster with the same level of investment (or alternatively grow just as fast while investing less), the rise of oligopolies has capped demand for funds and pushed rates lower.

Much of this trend is due to the rising importance of software and technology to our economy, which is hard to reverse. But part of it is also due to weaker antitrust regulation, which may change over time.

SELF-REINFORCING LOW RATES

When faced with the prospect of lower real interest rates and the desire to still have a long retirement, what do people do? Save more. That feedback loop from low rates to more saving has also likely put downward pressure on interest rates.

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?

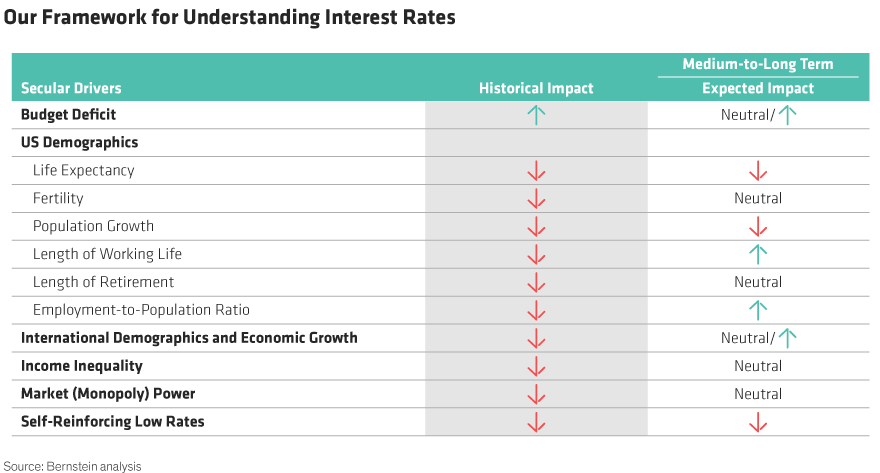

For the past four decades, only the budget deficit has had an upward impact on rates. All the other drivers have pressured rates lower.

Over the next decade and beyond, that pattern will change significantly. For the next 10 years, the budget deficit is expected to hold steady relative to GDP, which should neutralize its impact on rates over that time. While some of the other drivers will likely continue their trends, others are poised to stall or reverse, applying more upward pressure to rates and eventually causing them to rise (Display 3).

For instance, as people work later in life and maintain the same length of retirement despite living longer, they should have to save less each year, putting upward pressure on interest rates. Likewise, the increasing proportion of retirees in the economy will reverse the impact of the employment-to-population ratio, which should also press up on rates.

The same effects will likely be seen overseas, offset to some degree by the growth of India and Africa, whose populations will remain young for decades.

Income inequality and market power are wild cards. They could reverse dramatically based on geopolitical trends and populist movements. Or they could continue their multi-decade trends. For now, we believe it’s sensible to expect a neutral impact until there’s clearer evidence on policy changes.

Finally, low rates themselves could lead to more saving and more downward pressure on rates.

Overall, we see legitimate reasons for real interest rates to be at historical lows, to stay low for longer, and to eventually rise again over time. That may not be as dramatic as clamoring about the “mother of all bubbles,” but we believe this framework will help ground prudent investments going forward.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.