Now that the UK has avoided (at least for now) a hard Brexit as it negotiates to extend Article 50, investors might reasonably wonder whether they can relax for a moment and take stock of the bigger picture. What sort of longer-term future does the European Union (EU) have, irrespective of the UK?

A recurring theme of the Brexit narrative has been that the UK is negotiating from a position of weakness while the EU holds all the cards. Step outside that narrative and look at the EU from a broader perspective, however, and it cuts a less formidable, more fallible figure.

Brexit is one of many challenges the EU faces. At a fundamental level, the EU is struggling with the limitations to what a currency union can achieve without the support of a fiscal union, and the economic and political issues that such an anomaly can cause.

The economic issues are clearly visible in Greece and Italy, where lack of fiscal discipline has resulted in excessive debt. While non-EU countries might fix such problems through currency devaluation, this option is denied to Greece and Italy because of their euro area membership.

This has helped to create social tensions, the political consequences of which have included a rise in populism―a trend likely to become more entrenched if, as expected, populists gain ground in the European Parliament elections to be held in May.

These issues are important from a policy perspective―a fact that investors, in our view, should consider when looking at the EU longer-term. Ironically, the Brexit process, despite the EU’s apparent upper hand over the UK, has exposed some of the EU’s weaknesses in this respect. While for now euro area growth is low but stable, and political stresses remain under control, in future the EU needs to rise to a number of challenges if it is to continue on its successful journey.

No Feet of Clay, but Plenty of Baggage

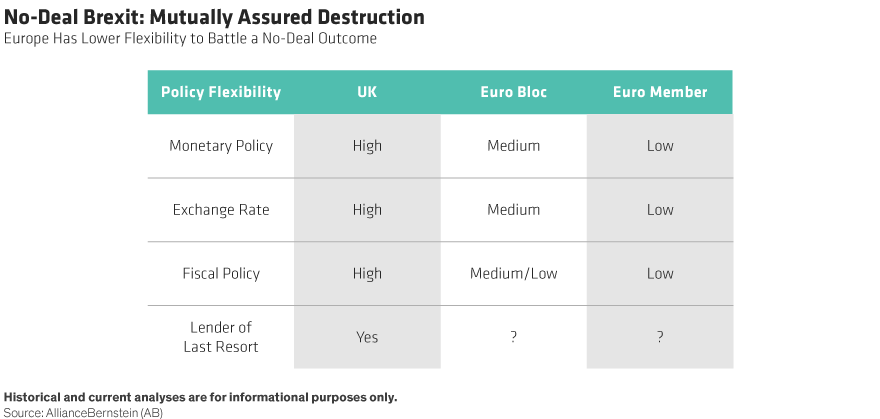

Although a no-deal Brexit remains an outlier scenario, in our view, reviewing the potential fall-out from this outcome is instructive. For example, we found that, while the UK would be the hardest hit, it would have more policy flexibility to deal with the consequences than the EU.

This was true for monetary, foreign currency and fiscal policy, and for recourse to a lender of last resort (Display).

In the case of monetary policy, for example, the policy rate is now 0.75% in the UK and -0.40% in Europe. The Bank of England (BoE) could cut to zero if necessary but the European Central Bank (ECB) would have to think carefully before cutting rates further into negative territory.

This is because negative interest rates are effectively a tax on banks: make them too negative, and they could act as a brake on economic growth. The ECB would also probably be unwilling to restart quantitative easing, which it ended only recently, while the BoE could restart it if necessary.

Weaker currencies can help economies, and our research suggests that sterling could weaken to around parity against both the US dollar and the euro. While the euro might also weaken against the US dollar, it would do so less than the pound, giving UK exports an advantage in that respect.

The EU’s lack of fiscal unity means that, while Britain could “turn on the taps” relatively easily, euro-area countries would have to reach agreement―not easy in a short time frame, especially when some countries (such as Italy and France) are already likely to be breaking existing rules.

As for lender of last resort: will the ECB continue to be the backstop if it thinks that the sovereign debt of weaker EU members needs to be restructured? The BoE has no need to consider such issues.

It would be an exaggeration to describe the EU as “a giant with feet of clay”, but it’s certainly carrying some baggage. How should these policy issues and the structural characteristics that cause them colour investors’ longer-term views of the EU?

Short-Term Opportunistic, Long-Term Cautious

We think it helps to look at the EU across two time-horizons―the short term, dominated by political risks such as those associated with Brexit and populism; and medium-to-long term, in which macroeconomic factors and the EU’s structure and policy limitations are more important factors.

In the short term, we think there are tactical opportunities, such as a firming of sterling and UK risk assets, at least while the threat of a hard Brexit appears to have receded.

Opportunities may also arise if the European Parliament elections trigger national polls. In one scenario, for example, we can see this happening in Italy, resulting in a more right-wing coalition with better financial credentials, which would be a boost for Italian government bonds.

Longer-term, however, we take a more cautious approach. Unless the EU somehow manages to achieve greater fiscal unity, it’s quite possible to imagine that a country like Italy―which is at risk of being downgraded to junk-bond status―may not be part of the currency union in five years’ time.

If that happens, Brexit will appear to have been less of an explosion, and more of a warning shot.

Sources: AllianceBernstein

For investment professional use only. Not for inspection by, distribution or quotation to, the general public. Current analyses do not guarantee future results.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time. AllianceBernstein Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.