Investors who want to reduce risk and maintain a steady income might consider a barbell strategy that pairs interest rate–sensitive bonds with high-yielding credit assets. But first, it’s important to strike the right balance.

Combining the two types of asset in a single strategy known as a credit barbell makes sense because the returns of each are usually negatively correlated. When riskier, growth-oriented credit assets such as high-yield bonds fall in value, government bonds and other interest rate–sensitive assets usually rise. A portfolio that includes both has the potential to weather most markets, as investors can rebalance by selling the outperformers on one side and buying the underperforming bonds on the other.

But what’s the right way to build a barbell? Would maintaining a simple 50/50 split between interest rate–sensitive and credit assets do the trick?

The answer will depend on each investor’s needs and comfort level. Let’s look at three potential barbell strategies that an investor might choose. For these hypothetical portfolios, we use US Treasuries to represent interest-rate risk and US high yield as a proxy for credit risk.

In practice, investors would want to diversify their portfolios with exposure to a wide variety of fixed-income sectors, including government bonds, bank loans, corporate and hard-currency emerging-market debt, inflation-linked bonds, and securitized assets.

GETTING THE BALANCE RIGHT

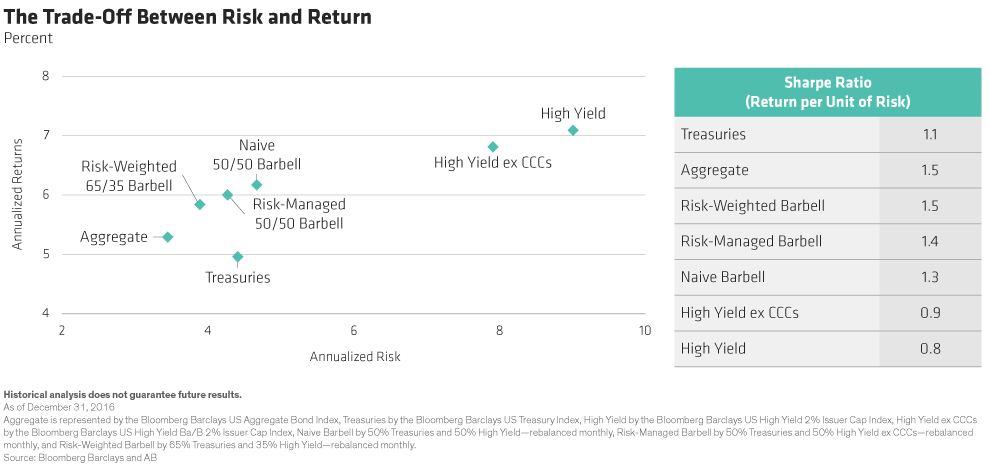

A simple 50/50 split between Treasuries and high yield might appeal to investors with high income requirements and a high risk tolerance. This is because credit assets are at least twice as volatile as high-quality government debt. So when it comes to risk exposure, an even market-weighted split between the two—we’ll call it the naive barbell approach—is actually tilted toward credit.

To reduce some credit risk, an investor might cut out low-quality, CCC-rated “junk” bonds, the riskiest slice of the high-yield universe. These securities are at the highest risk of default, and steering clear might make sense during the late stages of a credit cycle. This risk-managed barbell would give up a small amount of return in exchange for lower risk.

Investors who want to take the same amount of risk on each side of their income portfolio, however, would need to build a risk-weighted barbell. Because credit is at least two times riskier than rates, investors would have to hold more rate exposure to even out the risk weightings—roughly 65% in Treasuries and 35% in high yield.

The annualized returns and risks of each approach vary. But compared to Treasuries and high yield alone, all three of these hypothetical portfolios had better returns per unit of risk over the last two decades (Display).

It’s important, however, to actively manage the weights. Setting a static allocation and forgetting it won’t produce solid long-term returns. If the assets on one side of the barbell look expensive, a manager should be able to change the balance and lean toward lower-priced opportunities on the other side. If asset prices on both sides seem high, she may need to reduce overall portfolio risk.

RISING RATES DON’T HAVE TO DERAIL RETURNS

But how much rate or credit exposure is too much? For example, wouldn’t a 65% allocation to Treasuries or other interest rate–sensitive assets be too big in a rising-rate environment?

Not necessarily. Government bonds provide important diversification to credit exposure in all environments. But there are two other points to remember.

First, over the medium term, more than 90% of US Treasury returns come from the yield. That means rising rates can dramatically boost income for investors who are not primarily focused on short-term Treasury price fluctuations.

Second, rising rates ultimately lead to slower growth. When that happens, credit cycles fizzle out and growth-sensitive assets struggle. Eventually, slower growth causes interest rates to fall, allowing the economy to recover.

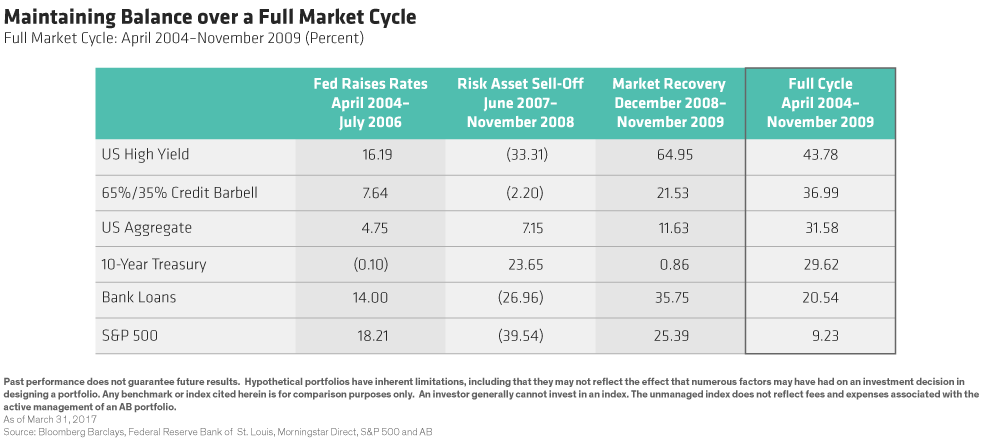

A 65/35 credit barbell would have comfortably outperformed a broad US bond market index and the S&P 500 Index between 2004 and 2009—a period that included 17 Federal Reserve rate hikes, the bursting of the housing bubble, the global financial crisis and an eventual market recovery. And it would have been within reach of the broad US high-yield market (Display).

There’s no one way to build a barbell. But it is important to vet potential managers carefully and learn about their investment process and approach to balancing interest-rate and credit risk over time.

Knowing which way to lean—and when—requires a deep understanding of the interest-rate and credit cycles around the world and how they interact. On a security-specific level, the ability to carry out intensive credit analysis on each security lets managers find the winners and—more importantly—avoid the losers.

Investing, like most things in life, is better with balance. A disciplined barbell strategy can create that balance in investors’ income portfolios.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.