Investors in FAANG stocks have enjoyed incredible gains in the past several years. During the decade between 2010-2019, Netflix has soared a whopping 3,972% while Apple has rallied 1,016%. Yet what seems like a windfall can also prove worrisome – especially if explosive growth leads to a lopsided portfolio.

Consider that a modest 2% position in Amazon initiated over that ten-year period would comprise over 25% of your portfolio today, all else being equal. Since reducing exposure will almost certainly trigger a large tax bill, you might feel trapped by your own good fortune.

How can you address the imbalance? Unfortunately, the usual ways all have drawbacks:

-

Holding avoids paying embedded capital gains taxes, but ignores the concentrated position

-

Hedging (e.g., through put options) works for short stretches, but tends to be expensive and requires constant monitoring and/or rebalancing

-

Selling reduces single-stock risk, but results in a hefty tax bill

For investors with longer time horizons, swapping the assets into an Exchange Fund may offer the ultimate solution: immediate diversification without the taxable transaction.

How Do Exchange Funds Work?

Exchange Funds allow subscribers to contribute one or more of their concentrated stock holdings into a limited partnership structure via private placement. In return, they receive shares that provide approximately 80% equity exposure against a broad market benchmark (such as the S&P 500 Index), and 20% exposure in illiquid assets like multi-family residential real estate.

Holding at least 20% of the partnership in illiquid real estate ensures that “exchanges” in and out of the fund are not deemed taxable by the IRS. That’s a critical provision—allowing investors to diversify, while continuing to defer taxable gains.

What about the other 80%? Stock contributions from incoming and existing investors are typically pooled as hundreds of securities into a diversified portfolio that are designed to closely track a broad market benchmark. As a result, not all stocks are accepted—only those that increase the fund’s exposure to a desired sector, or security. The equity allocation also tends to be managed in a highly tax-sensitive manner that seeks to minimize sales.

Upon exiting, during the first seven years investors usually receive the stock they contributed back first, although they may receive fewer shares if the fund has underperformed. If the fund outperformed the original stock, excess profits will come in the form of shares from a diversified basket of securities. Those willing to hold the fund longer than the typical seven-year lockup usually receive an additional option to redeem their entire investment via this diversified basket, effectively removing the concentration altogether.

Quantifying the Benefit

Let’s consider how a highly appreciated contribution of stock to an exchange fund would have performed relative to its immediate sale in the market. For this example, we’ll assume that seven years ago, an investor contributed a single concentrated position of XYZ Co. shares with a market value of $1M and a $100k cost basis. For simplicity, let’s propose that both scenarios—the exchange fund and the immediate sale—deliver a nominal annual return of 6% over the full period. With the immediate sale, the investor reallocates to a passive broad market strategy, at an annual fee of 0.25%, while the exchange fund’s fees are slightly higher at 0.85%.

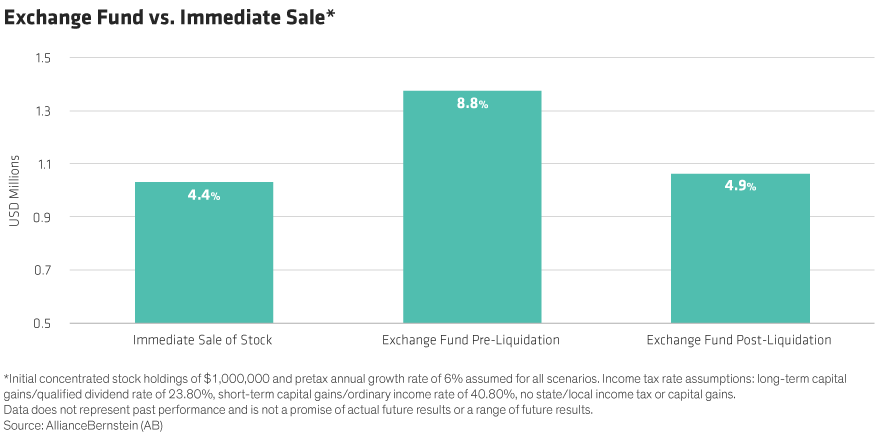

When selling the stock immediately, we assume reinvestment of the after-tax proceeds into a diversified portfolio, followed by a liquidation into cash at the end of the period. This scenario results in median growth of $1.03M over the seven-year time horizon, representing an annualized return of 4.4% (Display). By comparison, an investment in an exchange fund would reach $1.38M and generate an annualized return of 8.8% over the same period.

Keep in mind, this larger amount still includes embedded taxes; after-tax proceeds would net out at $1.06M, representing an annualized return of 4.9%. Despite higher annual fees, the value in the exchange fund exceeds that from an immediate sale because more wealth compounds while deferring taxes until the end of the period.

While some might find the differential modest, recall that we’ve also reduced the concentration risk while preserving upside potential. In other words, the portfolio is less susceptible to declines in a single, large position. Such risk isn’t out of the realm. Despite their dramatic growth, between 2010 and now, the FAANG stocks have each experienced periods with 30% declines.

Choosing the Right Fund

Around for decades, exchange funds have evolved into multibillion-dollar investment vehicles. But the landscape can be complex. When selecting a fund, investors should consider several important questions:

- 1. Will the fund accept my stock(s)?

- 2. Are there any liquidity concerns? Some funds enforce a partial seven-year lockup on profits.

- 3. How is the equity component benchmarked?

- 4. How has the fund performed relative to its benchmark?

- 5. What are the annual fees?

From our experience, exchange funds often provide the ideal combination of risk reduction and tax deferral. What could be sweeter?

The views expressed herein do not constitute, and should not be considered to be, legal or tax advice. The tax rules are complicated, and their impact on a particular individual may differ depending on the individual’s specific circumstances. Please consult with your legal or tax advisor regarding your specific situation.