China’s economy has slowed in the first part of 2022, weighed down by COVID-19-related shutdowns. We think the worst has passed at this point. Assuming that widespread shutdowns are a thing of the past, we expect Chinese authorities to take significant—and effective—steps to support growth in the second half of the year.

Fiscal Policy is the Key Driver…but Policy Coordination Matters

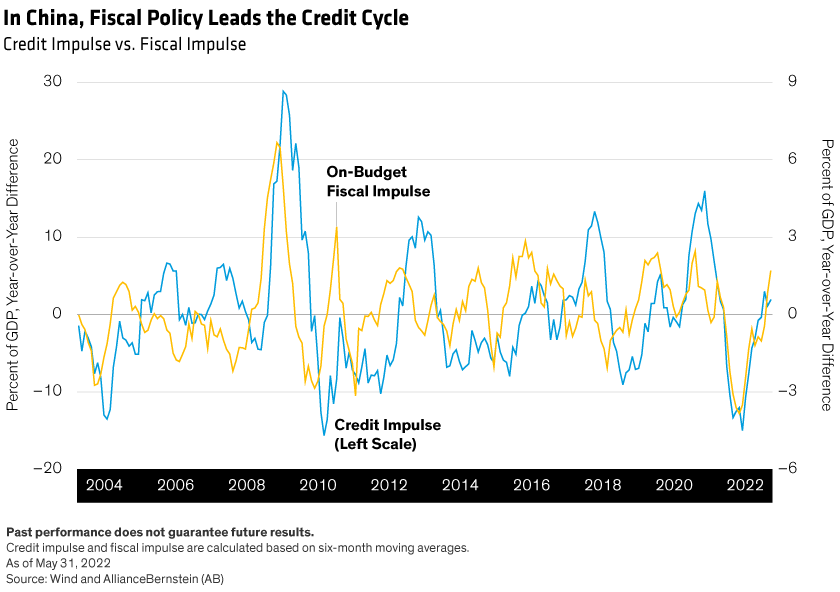

In contrast to Western economies, where monetary policy typically plays the lead role in stabilizing growth, we believe that Chinese fiscal policy is poised to do the heavy lifting this year. Several institutional factors make it more effective than monetary policy at stabilizing growth in the short run.

Despite decades of market-oriented reforms, the state-run sector remains sizable, encompassing the banking sector, local government financing vehicles (LGFVs)—major entities involved in infrastructure investment—and local and centralized state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

While SOEs tend to be less sensitive to interest rates and therefore to monetary policy, the state-run sector also enables China’s government to have a sizable—and efficient—impact on the real economy. This lever could speed the ramping up of infrastructure investment, both directly and by setting incentives for local governments and the banking sector to take part.

That’s not to say that monetary policy won’t play any role. China’s cyclical policy—particularly infrastructure investment—involves input from many ministries and several levels of government to move from design to implementation. So, monetary policy remains part of the mix, but several current factors could constrain its power. For instance, private-sector incentives aren’t strong right now, so monetary policy could end up “pushing on a string.” And while monetary-policy independence has increased in recent years with a more flexible exchange rate, external balances still matter.

The bottom line: fiscal policy does the heavy lifting in China (Display), but policy coordination remains critical for China to deliver an effective cyclical policy.

Delivering Enough Stimulus to Achieve the Desired Growth Rate

Except for 2020 (when the pandemic precluded an official growth target), China’s central government has essentially never fallen short of its annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth target, which provides an anchor point for desired growth. It uses cyclical policy—particularly fiscal—to fill any shortfall from other growth contributors.

The significant and unexpected shock from the latest COVID-19 outbreak has made it harder for China’s government to achieve its 2022 growth target, which many market participants thought was ambitious even before this year’s shutdowns. The pandemic effects also created uncertainty around the government’s desired growth rate—and accordingly policy support in coming months. This comes at a key juncture, because the government is also assessing policy and growth. The Politburo meets in late July—with second-quarter GDP in hand—to set policy for the months ahead. That session will be closely watched for clarity on the government’s thinking.

Our baseline 2022 growth outlook assumed that additional strong demand stimulus (especially through public investment) would be communicated in June or July. The government’s recently announced stimulus is encouraging, but not enough to push growth close to 5%. It’s possible that China’s leadership won’t announce policy support as sizable as we expect before the end of July. If that’s the case, it may suggest that the government could reduce the targeted growth rate—our best guess would be an effort to achieve average year-over-year growth in the second half that’s close to potential growth and the annual growth target. More policy support will still be needed even to achieve this lower growth rate, though a smaller amount than what we’re currently factoring in.

While we expect strong fiscal support, it’s important to keep this year’s policy measures in perspective. China’s policy-objective function has shifted from growth stability to balancing growth stability and financial stability. This would make a cyclical-policy overshoot less likely—and make it unlikely that the government will spend as freely—or boost growth as much—as it did during the GFC. In that episode, the government implemented an RMB¥4 trillion stimulus package, accounting for around 12% of GDP; this time, our baseline expectation is for a 5% increase in the broad deficit-to-GDP ratio.

Where Will the Money Come From?

China has many of the typical financing sources at its disposal, including general government bond issuance, tax revenue and fiscal deposits built up in prior years. China can also look to other sources, including local government special bonds, central government special bonds, policy bank support, LGFV bonds, shadow banking loans and land-sale revenue—each with its own nuances:

- Local government special bonds have become more important to infrastructure investment in recent years. In 2020, the government issued RMB¥1 trillion of central government special bonds. Our baseline forecast calls for an additional RMB¥2 trillion, beyond what’s already in the pipeline, to support public investment.

- Land-sale revenue will matter, though its relative importance has been declining. Not all land-sale revenue can be used for infrastructure, and the government only has discretion to invest around 25% of it.

- Policy banks are important government entities in China’s cyclical policy. In the 2015–2016 downturn, the central government established a special construction fund that helped stabilize growth. The government recently stated plans to increase policy banks’ lending quota by RMB¥ 800 billion this year, to roughly RMB¥2.5 trillion.

- LGFV bond issuance and shadow bank lending are highly correlated to market conditions, regulatory policies and risk appetite. This relationship highlights the importance of coordinated fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy in financing and delivering stimulus.

- On-budget financing sources are also tools in infrastructure investment: roughly 20% of on-budget spending is infrastructure-related.

In our view, China has many levers to finance infrastructure investment. If the central government is determined to ramp up infrastructure investment in order to boost economic growth, the hurdle doesn’t seem particularly challenging.

Spending Destinations: Where Will the Money Go?

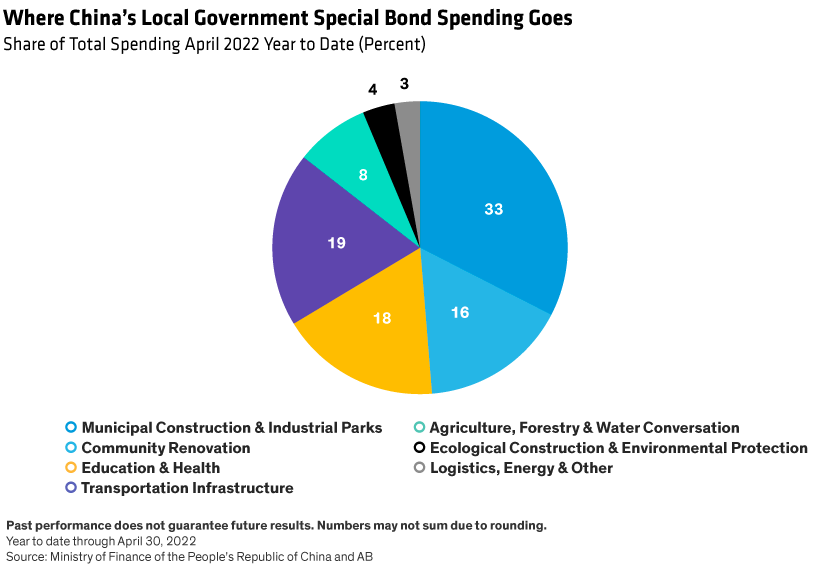

Much of the fiscal investment is likely headed for traditional destinations. For instance, about 70% of proceeds from local government special bonds are channeled to areas like transportation, municipal construction, government-subsidized housing projects, agriculture, forestry and water conservation, and the energy sector (Display). These areas broadly align with those mentioned in China’s latest policy package.

Meanwhile, spending in other areas has been on the upswing, including the environment, public health and urban utility, and “new infrastructure”—a recent spending priority directed mostly to information and communication technology. These new-infrastructure projects hold long-term benefit and are likely to grow faster than traditional infrastructure investment. However, given its small current share, it shouldn’t be counted on as a major cyclical lever to stabilize economic growth in the short term.

Ramped-up public investment and a rebound in Chinese growth in the second half of the year could help other economies—China could contribute the largest impulse in growth among major economies in the second half of the year versus the second quarter. Commodity exporters particularly stand to benefit—China accounts for roughly 50% of global metal consumption and 20% of energy consumption. That said, spillover impacts are likely to be smaller than during GFC, given the smaller scale and evolving composition of fiscal stimulus this time around.

The Big Picture: Policymakers Have Flexibility, and We Expect Them to Use It

China seems to have ample room to ramp up infrastructure spending. Official government debt isn’t particularly high—around 47% of GDP at the end of 2021, with central-government debt (20% of GDP) lower than local government debt (27%). Factoring in implicit local-government debt could raise the total debt/GDP ratio to around 60%, which is still not particularly high in the global context.

So, in our view, China has the near-term flexibility to expand infrastructure spending by leveraging up in what we see as an extraordinary time. The debt-to-GDP ratio might become elevated over the longer term if the country maintains its augmented fiscal deficit at the current level.

A pragmatic approach to this challenge might be to use expansionary fiscal policy when economic growth faces meaningful downward pressure (as we’re seeing now), and to consolidate fiscally when the economy is performing back in line with its potential. Chinese policy-makers have a history of looking at the long term, and we expect them to maintain that perspective, even while focusing on short-term growth for the next few months.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.