As we get ready to move into 2019, the macro backdrop points to a less favorable mix of growth and inflation at a time when central bank balance sheets are starting to shrink. Even if growth is simply returning to trend, the year ahead is likely to be more challenging—with populism and China looming as key downside risks.

Optimism Gives Way to Volatility During 2018

Entering 2018, there were high hopes that the global economy had finally shaken off the hangover from the global financial crisis (GFC) a decade earlier. Most cyclical indicators looked promising, and growth was highly synchronized across countries and regions.

This optimism didn’t last long. As early as the first quarter, cracks started to show in European economic data—cracks that have since spread to countries beyond Europe. Even stronger-than-expected US growth hasn’t been enough to keep global growth estimates from shifting to the downside. More worrying still, there’s now growing concern about China.

Why has the global economy slowed, and what lessons can we learn as we turn our thoughts toward 2019?

Slower Growth Ahead, but Simply Returning to Trend-Like

2017 was the first year since the GFC in which the global economy wasn’t rattled by some form of economic, political or financial shock. The relative calm helped growth move onto a firmer footing. Monetary policy remained supportive and the global trade multiplier was rising sharply, helping output growth to move to above-trend rates in many countries.

This year, those positive factors have gradually been eroded. The global trade multiplier has fallen back, and last year’s calm backdrop has given way to a period of advancing populist pressure—most notably in the form of rising trade tensions. And even though the overall mix of global policy still favors expansion, a shift toward more fiscal stimulus and less monetary accommodation in the US has pushed US Treasury yields and the US dollar higher. This situation creates headwinds for emerging markets.

Against this backdrop, it’s not surprising that growth has slowed almost everywhere outside the US. But it’s important to keep things in perspective: What we’re talking about for now is not a sharp slowdown or recession. It’s just growth returning to a more trend-like pace.

For many investors, a key question is what this step down in the pace of global growth is likely to mean for inflation and central banks?

Inflation Set to Drift Higher—Fueled by Populism

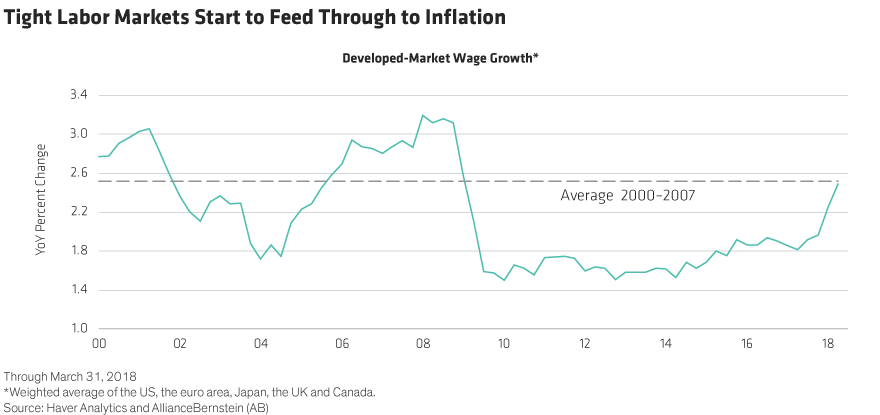

Because growth is unlikely to slow sharply and capacity use is already high, it would be wrong to assume that slower growth will automatically lead to lower inflation. One of the notable developments this year is that tight global labor markets have finally started to feed through into higher wage growth (Display). Apparently, the Phillips Curve still works.

But it’s not just cyclical forces that will shape the inflation outlook. As we noted last year, structural forces have weighed on inflation in recent years. From a demographic standpoint, a rising working-age population put downward pressure on prices, as did a flood of cheap labor from China—unlocked by globalization. Meanwhile, fiscal austerity and private sector deleveraging weighed on demand, helping to hold down inflation. Technology, too, has played an important role.

With the exception of technology, there are good reasons to think that these factors will be much less forceful in coming years. In some cases, they should soon start to exert overt upward pressure on prices. Globalization, for example, has begun to give way to populism—a trend that we believe will accelerate in the years ahead, becoming one of the key factors driving inflation higher.

Less Growth, More Inflation

In previous research, we’ve shown that all three populist channels—raising the drawbridge, institutional erosion and redistribution—are likely to lead to higher inflation. That’s because most populist policies can be thought of as negative supply shocks that push the growth-inflation mix in an unfavorable direction—more inflation for any given rate of economic growth.

The signs are already here. The Brexit vote in 2016 lowered the UK economy’s growth potential. Inflation stayed high even as demand growth started to slow, which helps explain why the Bank of England defied the market’s expectations and raised interest rates in August. In our view, rising trade tension should be viewed through the same lens as Brexit, and it will ultimately have much the same impact: slower growth and higher inflation.

The impact of this changing mix is reflected in revisions to our 2019 forecasts. In recent months, we’ve revised our global growth projections down to 2.9% from 3.1% but raised global inflation estimates to 2.8% from 2.6%. These are not big changes. However, they’re consistent with a shift toward a world that’s likely to see lower growth accompanied by higher inflation. Crucially, this scenario means that central banks may be less willing to respond as economic growth begins to slow.

That’s not a dynamic that financial markets are used to.

Systemic Risks: Populism and China Policy Mistakes

But populism isn’t just about rising trade tension. It can flow through many channels, all of which have the potential to make the economic and financial landscape more challenging.

Nowhere is populism a bigger risk than in Europe, which faces two threats in Brexit and the fiscal standoff between Italy and the European Commission. These two issues could become deeply intertwined—if the UK decides to leave the European Union without a deal, for example, the shock waves would be felt across Europe, adding to concerns about Italy’s debt sustainability.

China is the other big systemic risk.

Our current forecast is for Chinese growth to slow to 6.2% in 2019 from 6.5% this year. But it will require substantial and timely policy stimulus to prevent a sharper slowdown. If this doesn’t come, China’s growth could fall well short of expectations, sending a deflationary impulse through the global economy and commodity markets—especially if it were accompanied by a substantially weaker yuan.

US a Safe Haven for Growth?

In contrast to Europe and China, the US remains an island of calm. Tighter financial conditions and fading fiscal stimulus are likely to lead to slower growth in the year ahead, but we still expect above-trend growth accompanied by steadily higher inflation. If we’re right, the Federal Reserve is likely to continue raising rates at much the same pace as in recent quarters, 25 basis points a quarter.

In our assessment, risks to the US outlook look evenly balanced. If tighter financial conditions start to bite more quickly than expected or if softer global growth becomes a bigger drain on the US economy, the Fed would respond by slowing the pace of monetary tightening. But there are scenarios in which the Fed might be forced to raise rates further than expected, especially if inflation expectations start to drift higher.

Challenging Times Ahead in 2019

While we’re relatively confident in our US outlook for 2019, the year ahead looks like it will be a challenging one for the global economy. Growth is set to slow, inflation is likely to drift higher and downside risks cloud the outlooks in Europe and China. If either of these risks plays out, recession awaits. And this at a time when some central banks haven’t even started to tighten monetary policy—would they have anything left in their toolboxes?

But even if the global economy avoids these tail risks, 2018 has seen the initiation of a headline-grabbing trade war between China and the US. If it continues, the dispute could lead to a permanent shift in the global growth and inflation trade-off in an unwanted direction—especially if it’s a harbinger of a broader schism between China and the West.

All this drama is playing out with global debt levels still elevated and as central bank balance sheets are starting to shrink (Display). Net asset purchases by the Fed, European Central Bank and Bank of Japan have slowed to a crawl in recent months and are likely to turn negative over the coming year.

Putting the three key pieces of this jigsaw puzzle together—the global macro cycle, global liquidity and the secular threat from rising populism—we expect a volatile and more challenging year for global risk assets.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.