With the pound sliding to two-year lows, currency markets are signalling a higher probability of a no-deal Brexit. But the fallout from no deal would hurt the rest of Europe, too, and add to downward pressure on euro-area bond yields.

Much has changed since we wrote our last Brexit update in May: the UK has a new prime minister (Boris Johnson) and a new cabinet full of Conservative members of parliament (MPs) determined to leave the EU whatever the cost. But much remains the same: Brexit is no less complicated, the government is still weak and divided, Parliament is still against a no-deal exit and the EU is still opposed to reopening the withdrawal agreement reached with Theresa May.

Focused Strategy

Boris Johnson’s strategy is clear. The rise of the Brexit Party represents an existential threat to the Conservative Party which means his overriding priority is to deliver Brexit, come what may.

He has picked a cabinet to reflect this and will hope to convince EU leaders to compromise on the Irish border backstop so that the UK can leave the EU with a deal on October 31. If this fails, Johnson is willing to leave the EU without a deal and, to this end, has ordered his government to make detailed preparations for a no-deal exit (partly so the economy is prepared; partly to show the EU that he’s serious).

There are two major snags with this strategy. First, the EU is unlikely to agree to material changes to the withdrawal agreement and Irish border backstop (especially as it thinks it is better-placed to absorb a no-deal Brexit than the UK). Second, it is far from clear that Johnson would be able to get a no-deal Brexit through Parliament (and the EU knows this, weakening his bargaining position).

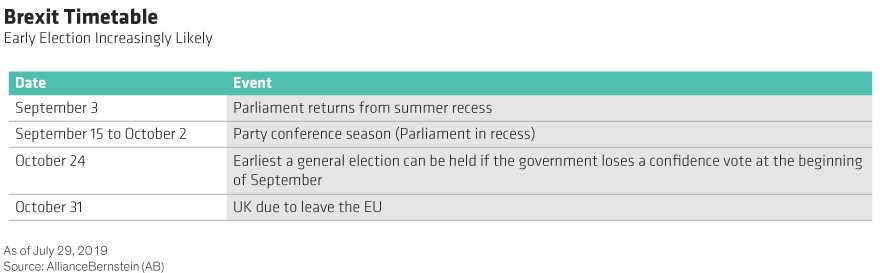

The second leg of Johnson’s strategy is therefore to prepare for an election at which the Conservative Party would campaign on a hard Brexit platform. In fact, an early election looks increasingly likely, either because the Conservative Party’s vote share starts to improve and Johnson thinks it would strengthen his position in Parliament, or because Parliament topples the government in order to avoid a no-deal Brexit.

Possible Paths Forward

While Johnson’s strategy is clear, trying to predict how things will pan out in coming weeks is less so. The following paths forward are all plausible:

1. The EU compromises enough on the Irish border backstop for Johnson to get a revamped version of the withdrawal agreement through Parliament, and the UK leaves the EU with a deal on October 31 (or shortly thereafter).

2. The EU refuses to change the withdrawal agreement, Johnson outmanoeuvres Parliament and the UK leaves without a deal on October 31.

3. The EU refuses to change the withdrawal agreement, Parliament outmanoeuvres Johnson and forces him to request another extension of Article 50 (it’s possible, though unlikely, that this would be rejected).

4. There’s an election, the Conservative Party strengthens its position and pushes ahead with a no-deal Brexit.

5. There’s an election, Parliament remains fragmented and there’s an extension of Article 50 leading to a second referendum, probably in the second half of next year.

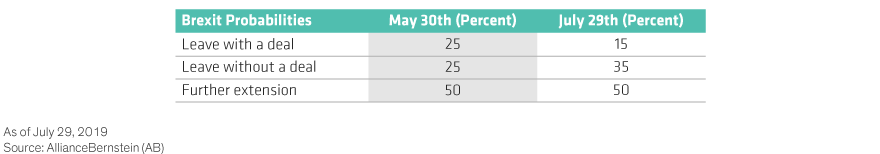

Brexit Probabilities

In May, we assigned a 25% probability to a no-deal Brexit. That now looks too low and we’re therefore raising it to 35%, lowering the probability of a deal to 15% and leaving the probability of a further extension of the withdrawal period unchanged at 50%. It’s also worth noting that an early general election now looks more likely than not.

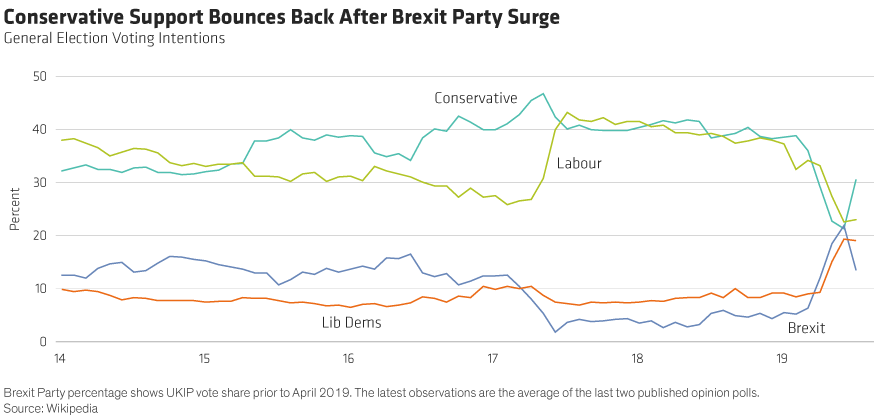

So why is the probability of a no-deal Brexit not higher? The main reason is that Boris Johnson does not have enough seats in Parliament to enforce his strategy. This could, of course, change and one of the key things to watch in coming weeks will be the Conservative Party’s opinion poll rating. Until recently, we had an unprecedented situation in which four parties were neck-and-neck at close to 20% in the opinion polls. This has changed in the last few days (see Display below), with the Tory Party starting to pull ahead as Johnson’s hard Brexit message begins to woo voters back from the Brexit Party. It’s not high enough yet, but if the Tories start to poll consistently around 35% and the pro-EU/referendum vote remains split between the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats, the appeal of an early election will rise and so too will the probability of a no-deal Brexit.

The most obvious casualty of rising no-deal Brexit risk has been the pound, which is now close to post-referendum lows against the dollar and the euro. The pound remains vulnerable—and could fall toward parity against the dollar in an adverse scenario—but the impact of a no-deal Brexit would be felt well beyond the UK’s borders, not least in the rest of Europe which is in no position to cope with the added burden of a disruptive UK exit (that’s certainly true for German carmakers). Yet another reason to expect euro-area bond yields to remain low or move even deeper into negative territory.

Darren Williams is Director—Global Economic Research at AllianceBernstein

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time. AllianceBernstein Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.