Just when you thought you’d seen it all in the financial markets, a little-known investment vehicle comes out of the woodwork. SPACs, or special purpose acquisition companies, garnered nearly as many headlines as cryptocurrencies last year. But SPACs aren’t new, nor do they comprise a large part of the market. So why the buzz?

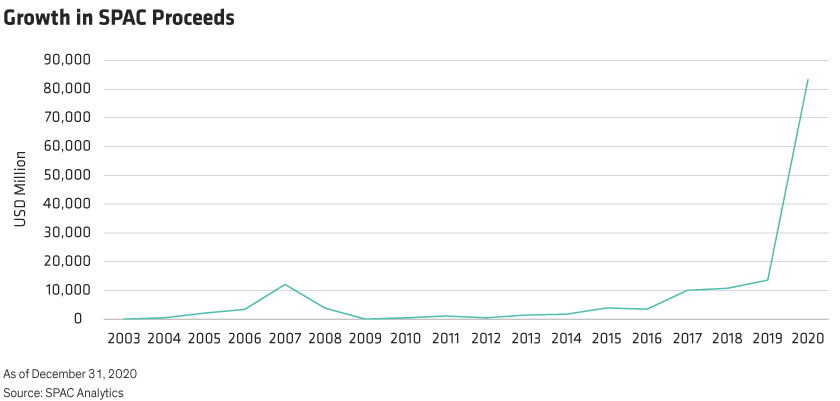

Nearly half of 2020’s IPO volume—more than $83 billion in blank-check proceeds—were SPACs1 (Display). While that’s more than six times greater than the previous peak, 2021 is shaping up to be another breakout year.1 But just because SPACs are sparking attention, should high-net-worth investors join in the fray? The answer lies in understanding how SPACs work, unpacking their historical performance, and comparing them to private equity.

What to Expect from SPACs

A SPAC is an acquisition vehicle designed to combine with a single non-public company. Essentially, SPACs bring their acquirees public via a “back door” that subverts the standard IPO process somewhat. Once the SPAC merges with its target, shares of the combined successor company then trade on an exchange like any other public stock (Display).

To reap the greatest benefit from a potential combination, individuals typically invest before the SPAC identifies a target, either by participating in the SPAC’s IPO or buying its shares in the secondary market. SPAC shareholders don’t know the identity of the non-public entity in advance, nor can they direct the SPAC toward a specific company. But they are protected if they don’t like a proposed deal or if the sponsor fails to finalize a merger in the allotted 24-month time frame; holders can redeem their shares at the trust’s value before the completion of the SPAC’s merger. In these cases, the SPAC returns the investor’s total pro rata share of the cash held in trust.2

The Short and Long of It

SPAC’s downside protection via their trust redemption option tends to lure short-term investors—typically hedge funds—to pursue a trading strategy: shareholders who never intended to own the combined entity either sell the SPAC in the secondary market above their initial cost basis prior to merger or redeem their shares at trust value. But the process for redeeming shares for trust value is detailed and requires experience to correctly execute.

Investors interested in holding the combined company over a longer-term horizon should weigh several other considerations, notably:

-

The blank check: SPAC shareholders don’t know the intended target in advance, nor are they under any obligation to combine with a company that is consistent with their stated objective. Also, while a trust redemption option is available to those that invest prior to the SPAC combination, there is no downside protection for investors who choose to stay invested in the listed successor company.

-

Sponsorship quality: Since each SPAC only undertakes a single merger, a weak or inexperienced investment team can cause a significant loss in shareholder value with the wrong deal. Successful SPAC sponsors use superior skill in vetting companies and determining appropriate valuations to generate strong returns.

-

Uneven playing field: Individual investors may not be able to secure primary SPAC IPO allocation, potentially increasing their cost basis and missing out on lucrative warrants given to IPO participants. Conversely, institutional asset managers—professional money managers for mutual funds, for example—can more often receive allocations for highly sought-after SPAC IPOs. Therefore, high-net-worth individuals interested in a long-term SPAC investments might be better off securing exposure through commingled investment vehicles—like certain mutual funds or exchange-traded funds—where they can leverage institutional scale.

SPACs Lack Luster

Despite recent high-flyers like Nikola, DraftKings, and Virgin Galactic—each of which is up over 300% from their IPO3—SPACs haven’t fared better than public stock indices historically. Since 2010, SPACs have consistently underperformed US small-cap companies by at least 10% in the year after completing their merger.4 Comparisons to alternate acquisition vehicles, namely private equity funds, are even more underwhelming. With its proven long-term strong performance, PE returns rank on par with or exceed returns from the US public market over nearly every investment horizon (from one to 30 years).5

The Match-Up: SPACs vs. Private Equity

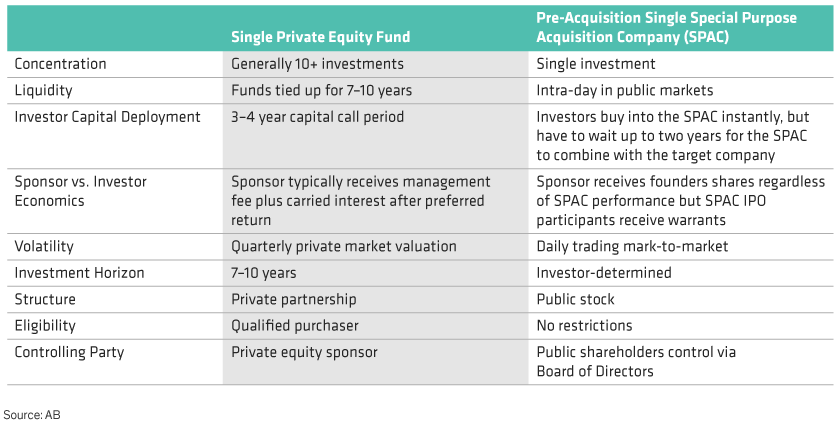

Like SPACs, private equity funds also focus on acquiring private companies, though they do so with a vastly different structure (Display).

-

Single company vs. portfolio approach impacts diversification. SPACs fire “rifle shots” into a single company, so business risk and trading volatility may be high. Conversely, private equity funds offer a curated diversified portfolio, typically with more than 10 investments

-

Fees not comparable and influence alignment. Private equity typically calculates carried interest—a type of performance fee—at the fund level after investors secure a minimum return on their investment (a preferred return). Private equity also takes a controlling interest and makes operational improvements over the 7- to 10-year life of the fund. Investors ultimately benefit from these enhancements—the better the portfolio company does, the higher the returns generally for the PE fund.

On the other hand, SPAC sponsors receive founder’s shares of each company, regardless of performance. So if investors attempt to mimic a private equity fund by compiling a portfolio of SPACs, they may incur high fees via share dilution. The difference is that SPAC sponsors receive founders shares even if the whole SPAC portfolio is down, whereas private equity charges its performance fee at the fund level by netting out the positive returns with the negative ones.

-

Diverging acquisition objectives. 2020 and 2021’s SPACs have heavily tilted towards growth-oriented companies and have a diminished focus on earnings quality or cash generation. Meanwhile, companies held in private equity funds are usually supported by cash flow multiples that tend to be in line or even cheaper than stock market indices.

-

Not quite dueling war chests. Despite the recent increase, the $87 billion of SPAC proceeds searching for acquisition targets remains very low relative to the $1.8 trillion of dry powder currently held in private equity funds. As such, SPACs face fierce competition for top acquisition targets.

A Better Alternative

While SPACs seem to be the flavor du jour, they don’t make sense for many investors. Instead, high-net-worth investors interested in making private company investments would benefit more from the diversification and aligned incentives of private equity funds with proven sponsorship.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice, or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.

1 SPAC Analytics

2 https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/11/19/a-sober-look-at-spacs/

3 https://spacalpha.com/insights/how-much-money-have-spacs-made-for-investors/

4 Klausner, Michael D.; Ohlrogge, Michael; and Ruan, Emily, A Sober Look at SPACs (October 28, 2020). Stanford Law and Economics Olin Working Paper No. 559, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper No. 20-48, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3720919 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3720919.

5 Bain PE Report 2020