The recent AB Disruptors webcast, “Unpacking the Debt Problem,” covered wide-ranging topics centered on the theme of governments’ debt burdens and their far-reaching implications. We fielded a number of follow-up questions from participants zeroing in on US government debt—no doubt spurred by the steady drumbeat of headlines about the debt-ceiling showdown.

Before tackling a few of these questions, it makes sense to quickly define the debt ceiling. It isn’t fiscal policy or new government spending; raising the debt ceiling is simply the process of authorizing payments for spending that’s already happened. This debate rears its head occasionally—most notably in 2011—but has yet to trigger a default. We expect the current impasse to follow a similar playbook to 2011, with the issue ultimately resolved.

But wrangling and brinksmanship makes markets edgy. Treasuries are still the risk-free asset underpinning the vast majority of our financial system, and the stability of the Treasury market is a significant underpinning of the dollar’s position as the world’s primary reserve currency. It’s understandable that investors are focused on the risk of an intentional default—or even a misstep and a technical default.

Let’s start with a question on the minds of some investors about the level of US government debt.

Is There a Tipping Point at Which the US Debt Burden Becomes “Too Much”?

The basic measure of a nation’s debt burden is the total amount of outstanding government debt divided by the size of the economy, as measured by total gross domestic product (GDP). The US debt/GDP ratio has topped out at around 100% during this cycle (Display), so—in basic terms—the country’s outstanding debt is worth about one year of economic output.

That burden may seem alarming, but there’s not really a tipping point beyond which debt would be too much. Japan’s debt/GDP ratio, for example, is closer to 300%, though it’s a special case. The presence of a bond-buying program has helped the country absorb its own debt, helping keep interest rates low for years. In some ways, the US is a special case, too. The dollar is the world’s main reserve currency, and Treasuries benefit from a safe-haven status that has helped suppress yields—and debt-servicing costs. This status has almost certainly enabled a higher US debt/GDP ratio than would otherwise be possible.

Affordable debt service is a key part of the ability to manage the outstanding debt burden. The US government doesn’t have to pay back more than an economy’s worth of debt every year—only the interest on that debt. Interest rates have been so low for so long that even as debt has steadily risen, the cost of servicing it remains very low by historical standards, at around 1.9% of GDP (Display). That’s not nothing, but neither is it the sort of ratio that should cause alarm, and in most respects, it’s a more important metric than the overall debt level.

A sustained, significant increase in US rates would make debt servicing more costly, but only gradually. That alone wouldn’t likely create a crisis, though it would be a growth headwind, as it would divert more government spending from otherwise productive uses.

The real worry, in our view, would be the longer-term implications of even a temporary default or breach of the debt ceiling, because so much of financial market activity is based on the idea that Treasury debt is sacrosanct. Even though the government will clearly retain the ability to make debt payments, if its willingness to make debt payments is called into question, it would pull a fundamental brick out from underneath the economy and financial system.

What Happens If Large Foreign Investors Start Selling Treasuries?

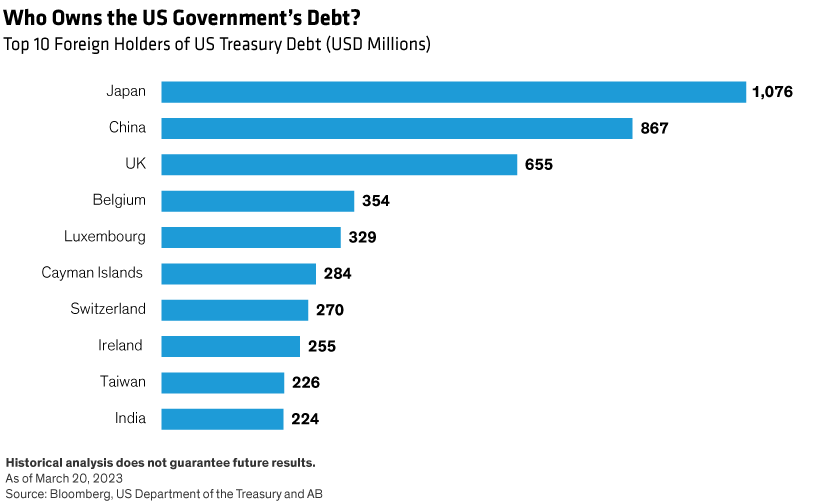

A good portion of outstanding US government debt—roughly one quarter of the total—is held by other governments. Japan, with over $1 trillion in US debt, and China, with more than $800 billion, lead the pack among US debtholders (Display), while the UK also has a sizable stockpile. This situation raises some concerns about the potential mass selling of Treasuries if foreign debtholders become disenchanted with how the US is handling its debt or debt policy—namely, if they start questioning whether the US is still willing to make its debt payments.

It’s true that the selling of many billions of Treasuries in such a way would most likely cause disruption, though the impact depends a lot on how much is sold. The effects include higher Treasury yields, making refinancing more expensive—since most government debt is shorter term. So, debt servicing would become more challenging, a challenge that could be magnified if the trigger were a default that led to a credit downgrade and a permanently embedded yield premium.

This type of scenario isn’t a new risk. It existed last year, five years ago, and even more so roughly a decade ago when the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis was unfolding. The debt-ceiling debate has intensified over the past couple of decades, while stopping short of default. We expect similar brinkmanship this year, with the US again likely to bump up against the date at which it truly runs out of money. The best way to avoid unwanted complications is to manage debt in an orderly way, sending a strong signal that the US is willing to service its debt.

Could a US Debt Standoff Tarnish the Dollar’s Reserve Currency Status?

Dating back to the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, the US has been the world’s leading reserve currency for central banks and large financial institutions, and the US has always paid its bills, underpinning the Treasury bond’s status as a safe haven. If the debt-ceiling battle were to deteriorate into a default and freeze up the Treasury market and other markets, it would threaten the symbiotic relationship between the dollar and Treasuries. Would the dollar’s appeal diminish enough to spur currency reserve managers to seek out other avenues?

To answer that question, we need to start with why the dollar has been the main reserve currency. It’s freely traded, and US authorities don’t manage its exchange value. It’s very liquid, with minimal transaction costs to buy and sell it against other currencies and a massive daily volume of trading activity. It’s supported by a large, globally important economy with a sizable liquid underpinning of financial assets to buy with it, and it’s supported by the world’s largest, deepest capital market. Reserve managers seeking to replace the dollar face something of a TINA (there is no other alternative) scenario, because the US dollar is the only currency that checks all the boxes. In the absence of other alternatives, the dollar is the destination.

But we come back to a common thread that runs through all these responses. It’s critical that the US continues to demonstrate not only its ability, but also its willingness, to pay the bills. This is the best advice for warding off any of the unwanted complications we’ve discussed here.

AB’s Disruptor Series is designed to provide distinctive perspectives on critical issues facing the capital markets today.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.