How should asset owners think about their future engagement with asset managers? We think that both external economic forces and internal investment-industry forces will change this interaction. What should asset owners want from asset managers? What should they pay for? The common view is that asset managers are under pressure, but over the next five years, we think asset owners may feel the same pressure, too—driving change in their investment approach.

As the industry answers these questions, we expect a rethinking of what the true investing benchmark should be and how to distinguish between active and passive, as well as a realization that in asset allocation, there’s no such thing as passive. We also think this will lead to a wake-up call for investors who are willing to pay a growing part of their fee budgets for alternatives, especially private equity.

Why Inflation Is the Only True Benchmark

Why does anyone buy an asset-management product? We assume that, ultimately, it must be to fund liabilities set in the real economy (including retirement costs, education and healthcare). All these things scale with the Consumer Price Index (CPI), or as a spread over the CPI. Yes, different cohorts of investors will face different rates of inflation, but the CPI is likely to be a closer match to those liabilities than a capital-market benchmark. Therefore, we think that ultimately inflation is the true benchmark.

In recent decades, a whole edifice of benchmarking has been built, mainly to measure outperformance relative to broad market indices. We’ll show below that this approach is outdated, given the growth in cheap factor exposure, but is still appropriate when deciding where to allocate fees. We argue that investors have lost sight of the point of benchmarking.

Benchmarking, relative to any capital-market index, exists to solve an agency problem, answering the question “Is it worth paying an active fee for this?” Such an exercise does not answer the more fundamental question of “Am I achieving the outcome I need?” Thus, we think that a combination of benchmarks is needed: inflation as the base for outcomes and capital-market benchmarks for determining whether to pay an active fee.

The Challenge of Lower Returns: Why It Will Be Harder to Beat Inflation

We think asset owners will face a more difficult outlook over the next 10 years than they have faced over the last 30 years. With hindsight (always a wonderful thing, of course), it has been relatively easy to beat inflation with exposure to stocks and bonds. However, we think there is a strong case to be made for having a lower return outlook from here.

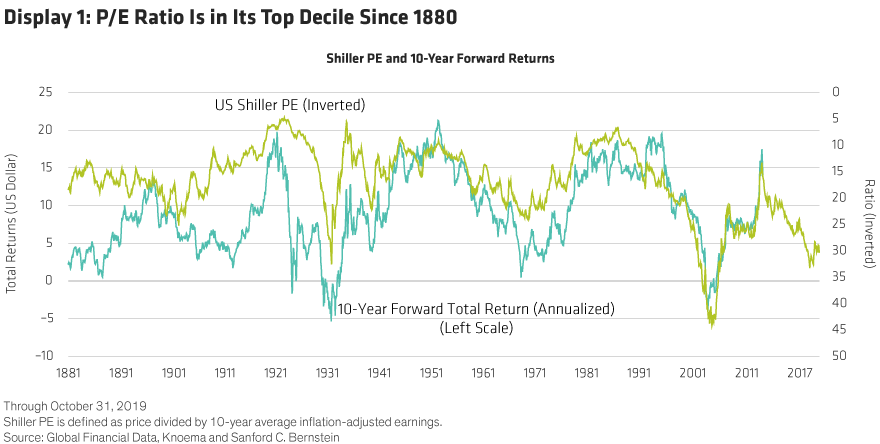

The basis for a lower return outlook is essentially the decline in yields across asset classes over the last 30 years. Specifically, the Shiller price/earnings ratio (price divided by 10-year inflation-adjusted earnings) is currently in its top decile since 1880 (Display 1). This matters because the Shiller PE is one of the best long-term equity-return forecasting tools at our disposal.

The current Shiller PE level implies an annualized return of only 4% on the S&P 500 Index over the next 10 years. One can argue that the Shiller PE hasn’t been as effective at forecasting in recent years because policy can override valuation, but at the very least its current level suggests that the range of expected returns should be lower over the next 10 years than it has been in recent decades.

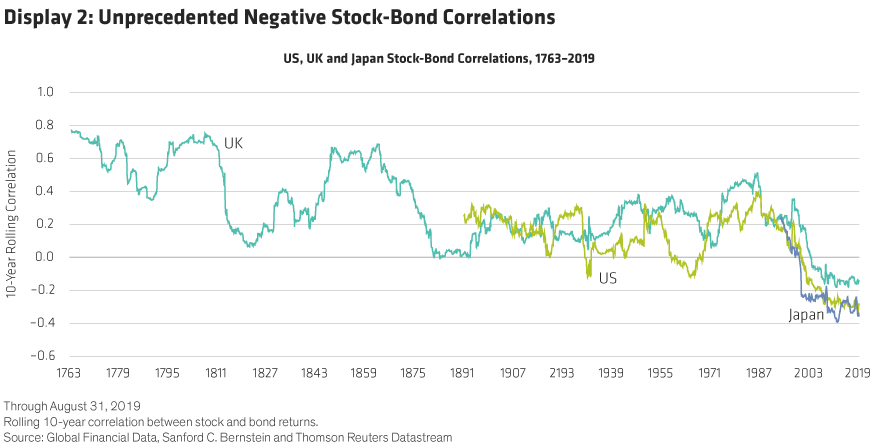

A further challenge comes in terms of diversification. The last 20 years have been an extraordinary period in which stocks and bonds have both gone up and beaten inflation and also achieved negative correlation. We show in Display 2 that this is unique in the context of the last 250 years. The reasons for the correlation being negative is beyond the scope of this article, but investors should not assume that it can continue. If the correlation between stocks and bonds were even zero, let alone positive, it would make it much harder to achieve diversification.

If we put these observations together, they have massive implications for allocation decisions. A common assumption is that, somehow, a 60% stock/40% bond allocation (or variations upon it) is a default, or even passive, decision when it comes to asset allocation. It is nothing of the sort. If the benchmark is a spread over inflation, then all asset-allocation decisions are active.

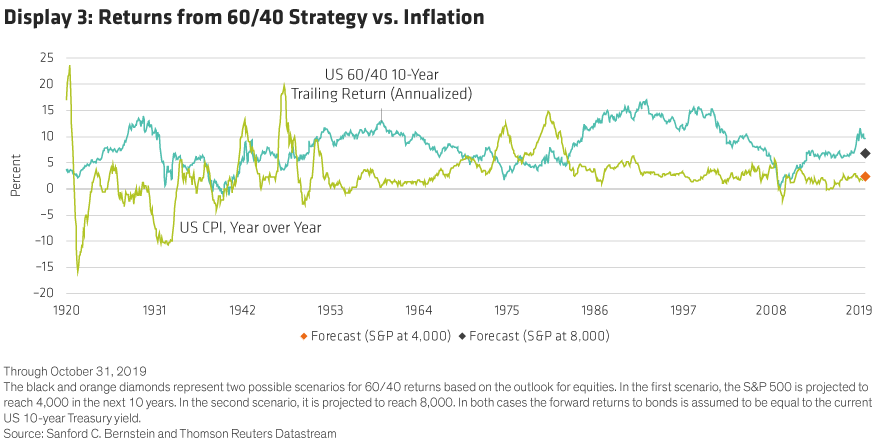

We can be more specific about what this insight means for a 60/40 allocation. In Display 3, we show the returns of a 60/40 strategy, with a 60% passive S&P 500 and 40% US 10-year government bonds allocation plotted against inflation. Over the last 40 years, the 60/40 strategy has beaten the US CPI by a wide margin. We think this is the main reason why 60/40 has become popular and investors have been lured into thinking it is passive. However, it has not always done so well relative to inflation.

The two diamonds on the right side of the Display 3 show two possible outcomes for 60/40, reflecting our low- and high-return forecasts for the S&P 500 over the next decade (we assume the 10-year forward bond return to be the current 10-year yield). Our low-return forecast has the S&P 500 getting to 4,000, in which case a 60/40 strategy would fail to beat current inflation. Even our very bullish 8,000 high-return forecast for the S&P 500 leads to a subpar 60/40 outcome.

This result informs the $5 trillion rotation from active to passive equity funds over the last decade. Some of this rotation was because too many active managers were charging active fees for delivering a return that was close to the index. But there has been a more subtle second reason. If investors can beat inflation by simply taking a 60/40 position in passive equity and bond indices, then why bother paying anything for active management? We suggest that this latter supposition will be challenged by likely market dynamics. A lower-return world with less diversification will require a different response.

The Changing Active-Passive Definition: Why Investors Should Pay for Only Idiosyncratic Returns

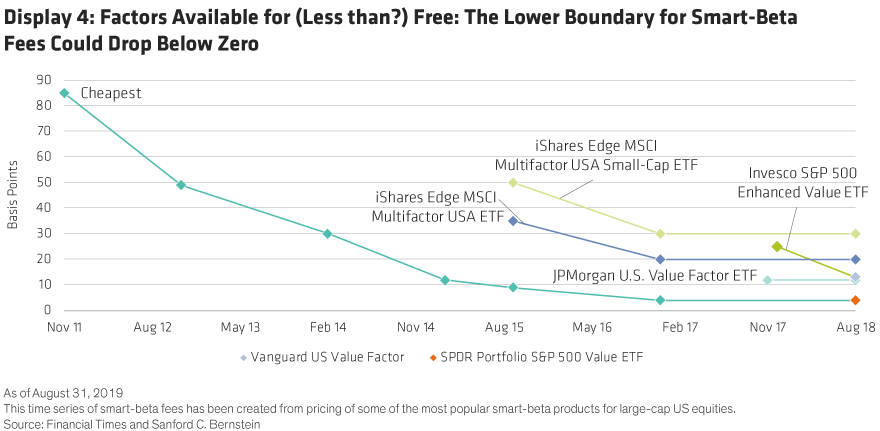

We think that a major force for change coming from within the investment industry is a redefining of active and passive—or alpha and beta. In the last few years, the fee for buying exposure to factors such as value or growth, or quality or low volatility, has come down. We show in Display 4 that the going rate for such products for US equity exchange-traded funds (ETFs) is now in the region of four basis points. It is not intrinsically more complicated to track a broad market index such as the S&P 500 than it is to track an index of value stocks, so we think the price point of these smart-beta products is going to fall to zero, or even below.

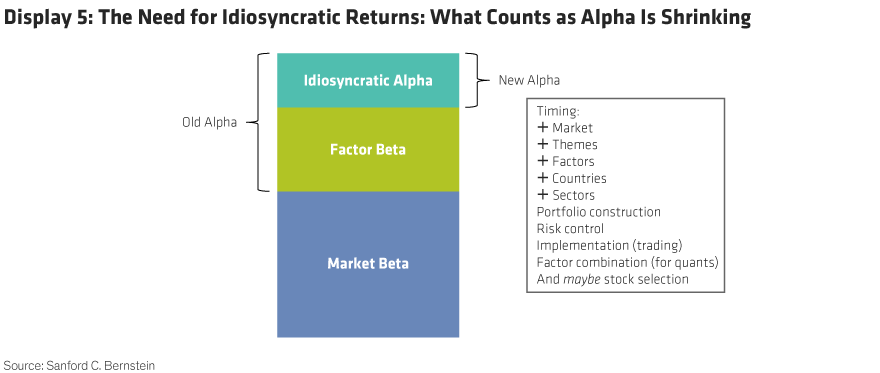

Investors have long understood that they don’t need to pay for broad-market beta. We suggest that they shouldn’t have to pay for static exposure to factor beta either. This effectively moves the dividing line between alpha and beta, as shown in Display 5.

We think that this shifting line makes it very clear what kind of returns are worth paying for. Asset owners should pay an active fee for returns that are idiosyncratic to cheap factor returns. In practical terms, idiosyncratic returns can be assessed by regressing fund returns on factors, with the choice of factors being determined by investments that are available, on a cheap and liquid basis, and that are plausible factor products that pension plan boards could buy as an alternative to active funds.

Our research on idiosyncratic returns also shows that these returns are more “sticky.” In other words, they are more persistent than normal alpha. Idiosyncratic returns can therefore help asset owners in their fund allocation decisions in a way that other metrics, such as “active share,” cannot. This principle is applicable not only to equities but also to fixed income and other asset classes.

The Alternatives Craze and What Happens Next

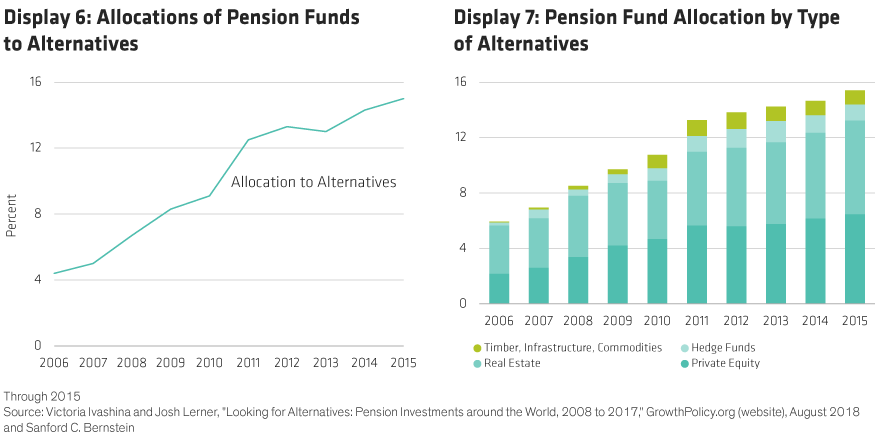

As investors have noticed the possibility of a future with lower returns and less diversification, one result has been a rush to allocate to so-called alternative investments, in particular private equity. As we show in Display 6 and Display 7, allocations to “alternatives” by pension funds and other asset owners have been rising in a linear way for over a decade.

In a sense, the reallocation to private equity could be justified by its historically high returns. Moreover, there is a structural wave of de-equitization, with the stock of listed developed-market equity shrinking from a combination of fewer IPOs, less secondary issuance and increased buybacks. Thus, asset owners who wish to earn the equity risk premium might feel the need to get more of it from private equity. The other thing that investors have often gotten right about private equity is the necessity of having a long time horizon that is often closer to the horizon of their liabilities.

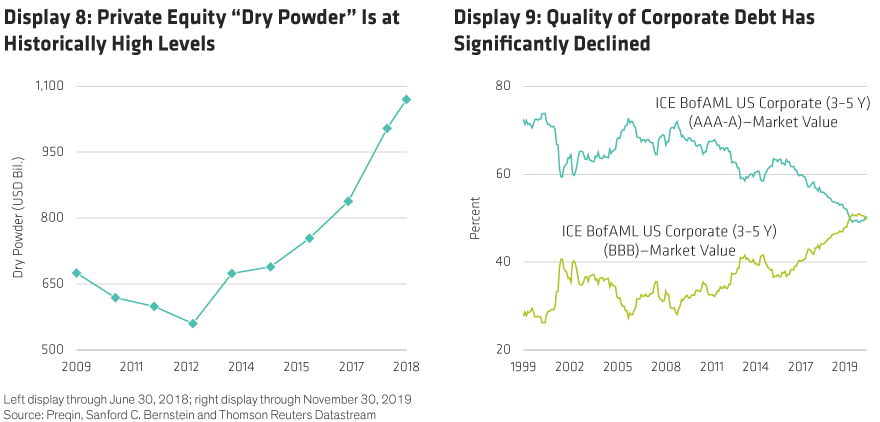

However, the positive reasons for the reallocation to alternatives end there. A major problem is that never before has so much been asked of private equity. We show in Display 8 that there is now “dry powder”—meaning committed but uninvested capital—of $1.1 trillion. This is far ahead of any level that we have seen before and will bid up entry prices, thereby reducing future returns.

Moreover, the entire history of private equity returns has been in an environment of declining yields and narrowing credit spreads. We show in Display 9 (above) that the quality of corporate credit is at its worst level in 20 years. More than half of investment-grade debt is at its lowest possible rating. Over the next cycle, we would expect credit costs to rise and thus to harm strategies that require access to leverage. In addition, as finding diversification becomes harder, we think that it is crucial not to confound lagged prices with diversification.

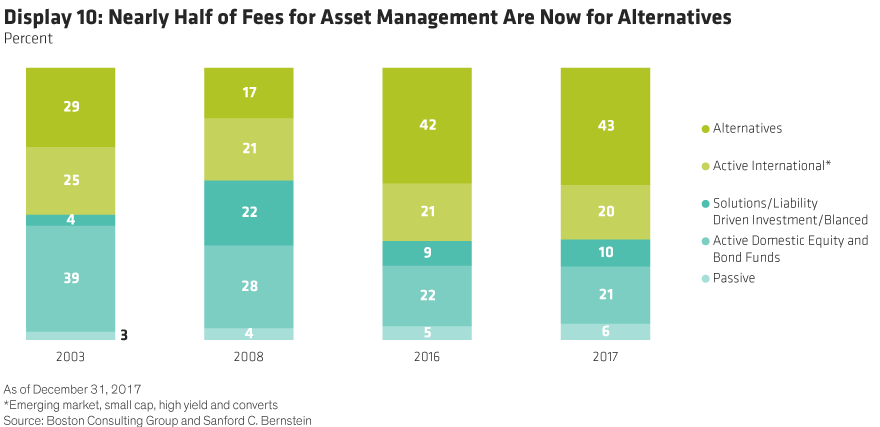

We can write as many papers as we like pointing out the likelihood that future private equity returns will be lower than past private equity returns. However, the reality is that the measurement of the outcomes and the way goals are set are so long term that it will likely take a long time before investors realize the scale of the problem. We think a more immediate wake-up call might come from fees. We are rapidly moving toward a world where most of US pension fund investment in public markets is via passive instruments.

At the same time, the main expression of active investing is happening in private markets. Given the different fee structure for alternatives, their share of the fee budget has now grown to over 40% of fees paid for asset-management services (Display 10). At the point when alternatives constitute half of fee budgets, we think that this might spark a greater questioning of whether the current structure of asset and fee allocation is the optimal one.

We think this state of affairs prompts a more fundamental question. The bigger mystery is why there is an alternatives versus non-alternatives distinction with different fee structures in the first place. Ultimately, governments and corporates have raised capital via a number of different kinds of instruments, and there are a range of investment strategies available in those assets. It is not at all obvious to us why labeling some of them as “alternative” helps asset owners. In fact, it can hinder efficient asset allocation and efficient fee allocation.

We think that the risk of a lower-return outlook in a cross-asset sense, a questioning of allocations to alternatives, and a recognition that 60/40 is not a passive basis for investment suggest that a better approach to asset allocation is needed.

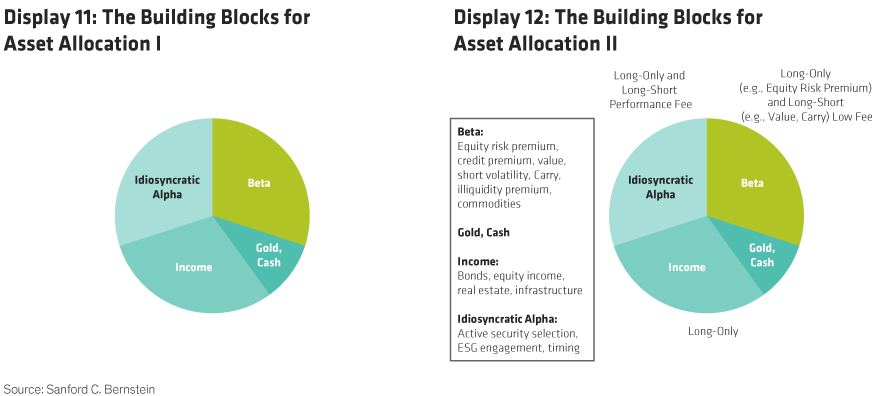

Rather than consider allocation in terms of asset classes, we believe that it can be helpful to think of it in terms of types of returns (Display 11). After all, the outcome that asset owners really need is a net-of-fee return; the types of assets used to achieve that are secondary. We would distinguish several types of return, including betas, which can be thought of as asset-class returns (a passive product on a broad market index); factor betas (a “smart beta” index offering exposure to value or low volatility); and returns to “risk premia” such as illiquidity risk. Then there are returns that constitute income.

Historically, the bulk of these returns have been in fixed-income products, but with so many fixed-income assets now offering negative real returns, we suggest broadening this category to include real estate and liquid stable-yielding equities (Display 12, above). There are also returns that we would classify as idiosyncratic alpha. The idiosyncratic point is crucial, as it distinguishes these returns from returns that can be achieved through exposure to factor betas. We explain what we mean by this in the next section.

There are several advantages to considering asset allocation in terms of return types. We suggest that this approach represents a more logical and fundamental way to differentiate sources of return, allowing for a more structured approach to fee allocation, with lower fees for betas and possibly performance fees for idiosyncratic alpha.

It also allows for a more structured way to compare the risks of strategies. We note that there is no separate bucket in this allocation for private equity. Instead, it is split between a beta for illiquidity risk premia and idiosyncratic alpha where there is skill. This does not mean that asset owners should never buy private equity, but that they should consider their returns as a combination of beta and idiosyncratic alpha components and assess the fees they are willing to pay for those parts.

Conclusions for Asset Owners

The rotation into passive strategies and alternatives in recent years has been in part a response to exogenous market forces and in part a response to innovations within the asset-management industry. However, these trends represent an incomplete process. We think that the next stage of industry evolution will involve a rethinking of the relationship between asset owners and asset managers.

The first step of this process will be realizing that for many end beneficiaries, it is inflation that is a key benchmark, and that inflation is likely to become harder to beat. We think that this realization will prompt a move away from the assumption that 60/40 is somehow a default or passive approach to asset allocation. Currently, alternatives are seen as a solution to this problem, but we think that the net-of-fee return on private equity, in particular, is likely to disappoint.

An important source for change in the relationship between asset managers and asset owners will, we think, be in greater differentiation between the value of different types of return streams. The abundance of cheap products that deliver factor returns has a significant impact, moving the dividing line between what counts as active and what counts as passive. If factor exposures are available for a zero fee, then we think the goal of an active fund becomes the delivery of idiosyncratic returns. This allows for a much sharper focus on which return streams are valuable.

This leads to a different approach to asset allocation. We suggest that, ultimately, all asset allocation is an active decision. In a lower-return world, and where the active-passive distinction changes, we suggest that asset owners would benefit from thinking about allocation between betas, idiosyncratic alphas and income. Asset owners face a challenge in delivering returns that can beat inflation over the next 10 years. We think that this new approach to investment could be instrumental in facing up to that.

Inigo Fraser Jenkins and Alla Harmsworth are Co-Heads of Portfolio Strategy at Bernstein Research.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.