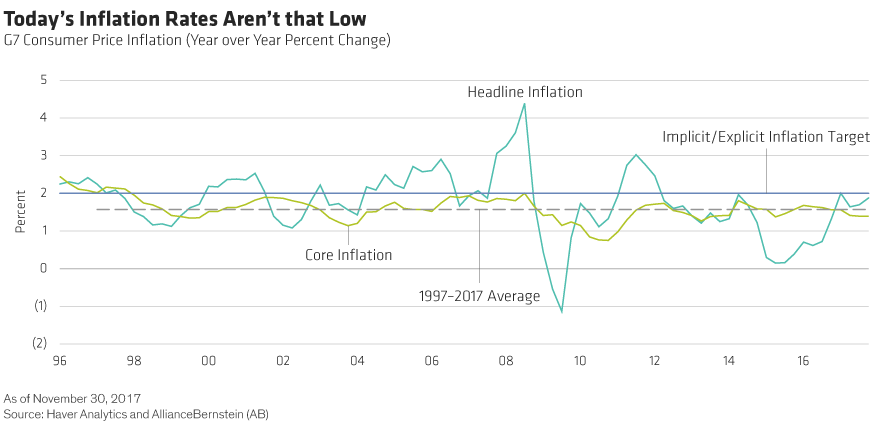

The best way to see this is by looking at the core inflation rate—inflation excluding food and energy prices (

Display). For major developed economies, core inflation is currently 1.4%. That’s pretty much the same as the average over the last 20 years (1.5%) and not much below the average for the 10 years before the global financial crisis (1.6%).

The picture is very similar for headline inflation: it’s currently 1.9%, slightly higher than the 1998–2017 average of 1.7% but the same as the pre-crisis average.

Core inflation has also been remarkably stable over the last 20 years. With two very brief exceptions, inflation excluding food and energy has fluctuated in a narrow range between 1.0% and 2.0% since January 1998 and has been above 2.0% just once (at the peak of the last cycle in August 2008). The lack of inflation volatility is all the more surprising given the large swings in economic activity during that period. All told, inflation hasn’t been very cyclical in recent years.

The Phillips Curve Isn’t Dead—But Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

Understanding inflation requires both a cyclical and structural perspective.

Does this lack of cyclicality mean we should abandon the Phillips curve? In our view, the answer is no. We think the theory behind the Curve still makes sense—at least as a partial explanation of inflation.

And most of the evidence still broadly supports the theory. Comparing annual developed-market core inflation to the global output gap between 2000 and 2017 shows a clear positive relationship between the size of the output gap and core inflation, which is consistent with Phillips curve theory. The bigger the output gap, the higher the rate of inflation.

But the relationship isn’t particularly strong, suggesting that other factors are at play. And it takes a big change in the output gap to have a material impact on core inflation—in other words, inflation isn’t that responsive to business-cycle changes.