The coronavirus outbreak has hit the nonprofit sector hard and many are struggling to stay afloat. Private foundations inundated with new funding requests face equally daunting concerns. Between the two, one cohort may be losing sleep at night: board members overseeing the investments of mission-driven organizations. With market gyrations likely to persist—and uncertain times ahead—many are asking, “What should I do now?”

Having already outlined nonprofit board members’ and Investment Committees’ fiduciary duties, let’s focus on how board members can carry them out in today’s unsettled environment. The first step for decision-makers? Meet (virtually) with your investment advisor. Review the current asset allocation and Investment Policy Statement—if there is one—and determine whether the portfolio complies. Understand the rationale for any deviation and make a record of the discussion.

At this point, board members should seek to address two critical questions:

- Should the organization maintain its existing asset allocation?

- Should spending from the portfolio be increased or reduced?

Both answers flow from a careful assessment of the organization’s overall financial health. Has the crisis changed its time horizon, need for liquidity, or investment objectives? If so, then the asset allocation policy should be updated to reflect these. In most cases, however, the long-term asset allocation deemed appropriate at the outset likely still applies. In times of turmoil, rely on your Investment Policy Statement. The only thing that should change a long-term asset allocation is a change in the organization’s long-term plan.

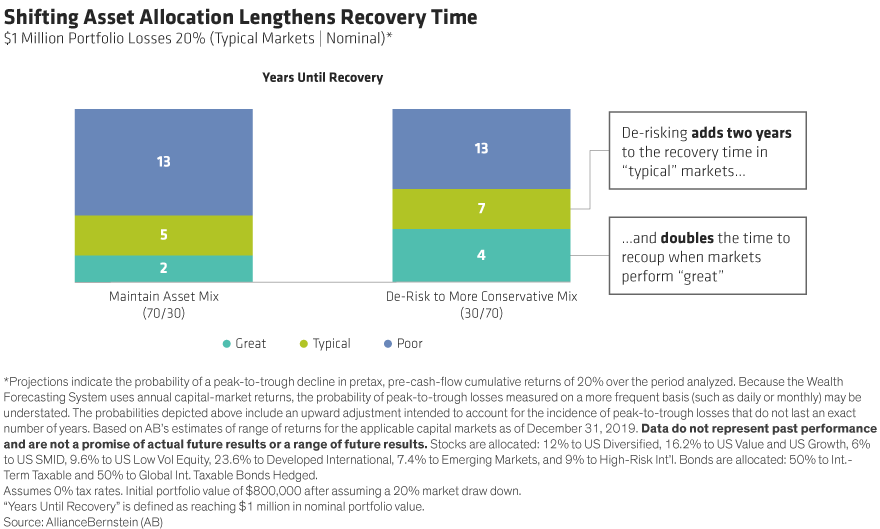

Besides, nonprofits that de-risk during bear markets extend the time required to recoup their losses (Display). Consider a $1 million portfolio that has declined 20% to $800,000. In “typical” markets, the organization could expect to recover these losses in five years—assuming it maintains its current 70/30 (stock/bond) allocation. But by de-risking to 30/70, the time to recover stretches to seven years. Even if markets bounce back more quickly (i.e., “great” markets), as they’ve historically done, de-risking would double the time to recovery from two years to four.

Staying the Course Doesn’t Mean Standing Still

Decision-makers should also note (in writing) how their investment advisor is responding to the current environment. For instance, some managers adjusted exposures tactically in response to changing market conditions. Some rebalanced, while others held off as bid/ask spreads widened.

Your spending policy also merits re-evaluation. To avoid selling assets at depressed prices, nonprofits that can defer spending should consider delaying or temporarily reducing scheduled portfolio distributions. Prior to the crisis, some nonprofits had established short-term reserves (typically 3–6 months of operating expenses). These reserves can serve to bridge the gap in emergencies like the one we are facing today.

Other organizations will need to tap their long-term portfolio for regular distributions. For those, applying a “smoothing rule” may prove beneficial. Smoothing sets annual spending as a percentage of the average of several years’ asset values rather than just one year. For example, basing spending on a percentage of the 12-quarter rolling average value of the portfolio allows organizations to adhere to their long-term allocations while spending through the dips and mitigating volatility in distributions.

Spending More Is An Option

Unfortunately, many nonprofits face a more acute need to draw on their portfolios. For some, it’s a matter of survival. Others face an age-old dilemma: spend more to increase impact on the community today or preserve a shrinking portfolio for tomorrow. In many cases, an organization can make an outsized distribution today without devastating its long-term impact—if it stays disciplined in the future.

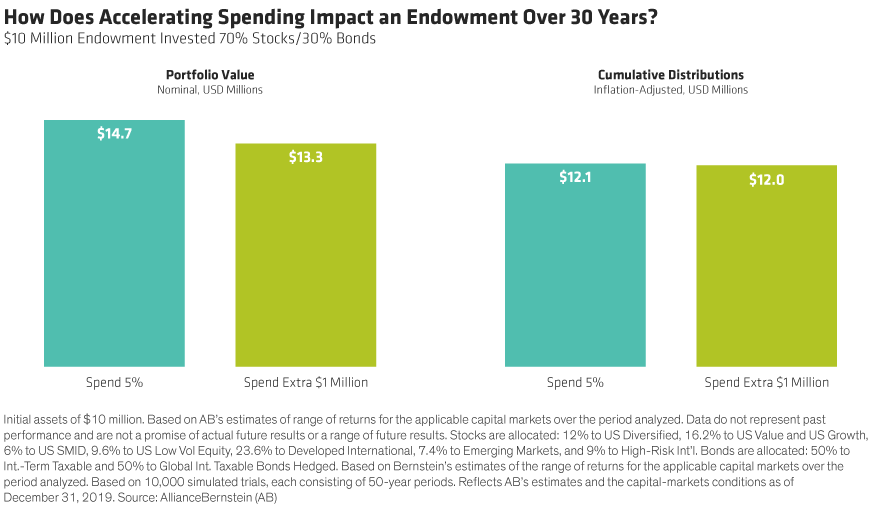

Consider a $10 million endowment invested 70/30 (stocks/bonds) that distributes 5% per year. Over 30 years, the endowment would grow to $14.7 million in typical markets after distributing $12.1 million cumulatively in today’s dollars. But what if the board decides to withdraw an extra $1 million this year, on top of the planned distribution, and then return to the regular 5% spend rate next year (Display)?

In 30 years, the endowment would grow to a median value of $13.3 million. While the outsized distribution lowers the ultimate portfolio value from $14.7 million, it still ends up 33% higher than today. More surprising? With $12.0 million of cumulative inflation-adjusted distributions, the initial $1 million withdrawal has virtually no impact on total spending over three decades.

Some Wiggle Room

To protect the long-term health of the portfolio, board members should recognize that an extraordinary withdrawal today essentially represents an acceleration of future distributions. If the percentage spending rate remains the same, next year’s withdrawal—on an absolute dollar basis—should be lower to compensate.

Nonprofit board members must also be mindful of applicable laws. If the withdrawal comes from unrestricted reserves that are currently expendable, the board has great flexibility. Other funds, however, may be subject to donor restrictions or considered part of a permanent endowment.

The Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA) guides nonprofit investment decisions and endowment expenses1. It states that—beyond certain exceptions for donor intent and specific purpose of funds—decisions about investing and spending must be made in good faith under a standard of prudence.

An institution may spend as much of an endowment fund as it deems prudent for the purposes and duration of the endowment. However, UPMIFA suggests spending above 7% may be a red flag. In practice, many institutions with permanent endowments aim to preserve the purchasing power of the principal over the long term, which often leads to spending rates in the 3%–5% range. Private foundations are subject to a minimum 5% distribution but have the flexibility to grant more. Those that wish to increase grants today can take comfort that a distribution in excess of the required 5% may be carried over and used to reduce distributions for five more years.

In short, board members must heed their fiduciary duties, but their hands aren’t tied in this time of need.

1 UPMIFA has been adopted by all states except for Pennsylvania.

For more on timely topics for nonprofits, explore “Inspired Investing,” a Bernstein podcast series that covers investing, spending, policy, and more. For Endowments & Foundations, and for additional thought leadership, check out the related blogs here.

The views expressed herein do not constitute and should not be considered to be legal or tax advice. The tax rules are complicated, and their impact on a particular individual may differ depending on the individual’s specific circumstances. Please consult with your legal or tax advisor regarding your specific situation.