Individual retirement accounts (IRAs) have historically offered coveted tax deferral opportunities. Recently proposed legislation, however, may limit this benefit for inherited IRAs. This potential tax deferral loss is alarming, but just how much of an impact would this change really have?

Under current law, non-spouse beneficiaries can “stretch” inherited IRAs over their lifetime by taking required minimum distributions (RMDs) based on their remaining life expectancy. The Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, though, proposes to limit the deferral period for inherited IRAs to just 10 years.

Overview of the SECURE Act

The SECURE Act passed the House with bipartisan support in May, but the Senate has yet to take a vote on a similar bill. The bill proposes several welcomed changes to the required minimum distribution rules including a repeal of the maximum age for traditional IRA contributions which would allow participants over the age of 70½ to continue making contributions to IRAs if they are working past traditional retirement age. Additionally, the age that required minimum distributions start would increase from 70½ to 72.

Unfortunately, news coverage on these welcomed changes has been overshadowed by the attention that the proposed elimination of the stretch IRA for most beneficiaries has garnered. Specifically, the House bill would require retirement accounts to be completely distributed and taxed by the end of the tenth calendar year following the participant’s death. The Senate version of the bill has a similar provision. There are exceptions to this rule, which are discussed later in this blog (see Exceptions and Unintended Consequences)

. . .

What is tax deferral worth?

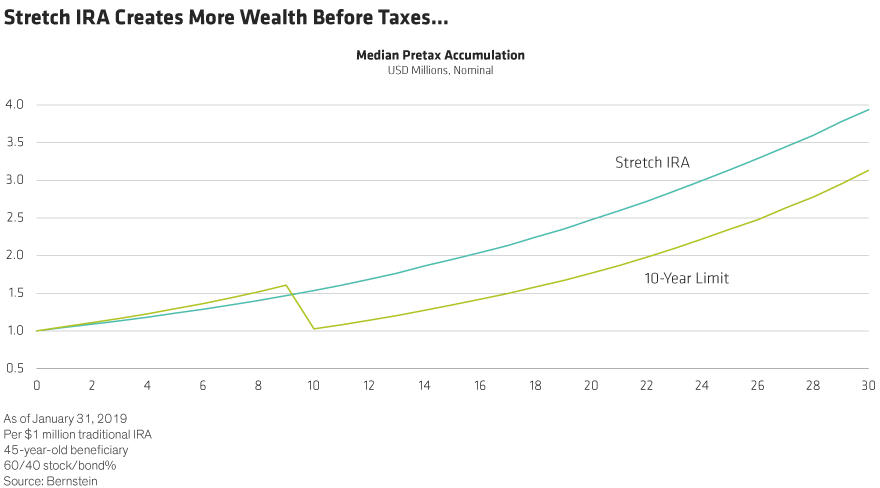

To quantify the potential cost of losing the tax deferral on an inherited IRA, consider a $1 million IRA left to an individual beneficiary who is 45 years old. This beneficiary invests in a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds (Display).

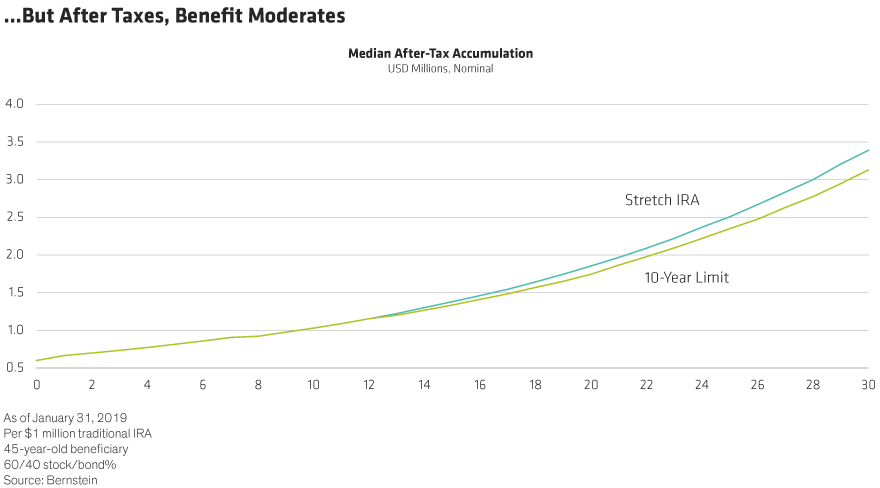

On a pretax basis, the stretch IRA generated more wealth—80 basis points more per year, or 26% more wealth over 30 years—than the 10-year limit proposed by the SECURE Act. When the analysis is adjusted for the income taxes, a much different picture starts to emerge (Display).

In this case, we are displaying the liquidation value of the inherited IRA each year in order to fairly compare the two scenarios on an after-tax basis. After making this adjustment, the true benefit of tax deferral decreases to 28 basis points per year over 30 years, or just 8.3% of total wealth. The steep decline after adjusting for taxes can primarily be attributed to a higher income tax rate for the deferred gains.

In a balanced portfolio of traditional investments like stocks and bonds, much of the investment return consists of capital gains and qualified dividends, which are normally taxed at 23.8%.* A stretch IRA forces capital gains and qualified dividends, which are taxed at a lower rate, into ordinary income when distributed in the future, which is taxed at a higher rate. If the investor has a sufficiently long time horizon—over 15 years in this case—the compounding effects of tax deferral will eventually overcome the tax rate differential to provide more after-tax wealth. But before 15 years, the benefit of tax deferral is lost.

Exceptions and Unintended consequences

The 10-year requirement would not apply when the beneficiary is the surviving spouse of the participant, a disabled or chronically ill non-spouse individual(s), an individual(s) not more than 10 years younger than the participant, or minor children. For minor children, the 10-year requirement would begin once they reach the age of majority. In cases where the participant fails to name a qualified designated beneficiary, however, an IRA would still need to be fully distributed within five years of the participant’s death (when death occurs prior to the required beginning date for RMDs)—this is consistent with the current law.

The SECURE Act could also have unintended consequences when retirement assets are left in trust instead of directly to individual beneficiaries. Under this bill, some trusts may not meet the requirements for a payout over the beneficiary’s life expectancy. Even when a trust qualifies under current law, it may fail to meet the new requirements that would be imposed under the SECURE Act. This is because unless all of the beneficiaries are minor children, or disabled or chronically ill individuals, the deferral will likely be limited to 10 years.

The one exception may be a conduit trust. This is by far the most prevalent type of IRA standby trust today because it is guaranteed to qualify as a see-through trust. But this structure requires that all distributions from the retirement plan are immediately disbursed to the beneficiary. As a result of this distribution requirement, inherited IRAs left to the chronically ill or disabled are often in the form of an accumulation trust instead of a conduit trust. In many cases, structuring the trust as an accumulation trust is essential so the assets do not push them beyond the means-test threshold, disqualifying them from public services. Additionally, few if any estate plans in place today, containing standby conduit trusts, have contemplated a mandatory lump sum distribution immediately or within 10 years to the trust beneficiaries. In fact, mandatory distributions tend to run counter to the goals and objectives of the trust.

Planning for the unknown

New legislation, whether it’s the SECURE Act or some derivation of it, will likely reduce the advantage of using a stretch IRA to defer taxes on retirement assets. However, after adjusting for accumulated income taxes, the stretch IRA may not be as beneficial as expected and losing it may not be as detrimental to forecasted wealth. So before taking drastic steps to preserve the tax deferral of an inherited IRA, first understand the real after-tax value at risk. If the SECURE Act becomes law, then it will be important to ensure that beneficiary elections and testamentary trusts created by a will or revocable trust fully contemplate the implications of a mandatory lump sum distribution within 10 years of death for beneficiaries.

* Consists of a 20% federal capital gain rate and a 3.8% tax on net investment income.

To read more about the current law and benefits of a stretch IRA, read our blog, “Should You Leave Your Retirement Accounts in a Trust?”

The views expressed herein do not constitute and should not be considered to be legal or tax advice. The tax rules are complicated, and their impact on a particular individual may differ depending on the individual’s specific circumstances. Please consult with your legal or tax advisor regarding your specific situation.