Whenever a particular asset class suffers through a period of difficult performance, the financial pundits set off their warning sirens and announce that the end has come. These headline-grabbing predictions make for good press, but they’re almost always wrong. Hedge funds are the current target of the pundits, as they have been from time to time over the years. But the pundits have been wrong before, and we think they’re wrong again.

Recent Results in Perspective

One of the early predictions of doom came in a January 1970 Fortune article, “Hard Times Come to the Hedge Funds.” After a difficult year for hedge funds in 1969, the article cited a host of commentators who argued that there were too many funds, too much money in the industry, and too many managers crowding into the same trades. Many managers, including Warren Buffett, closed their funds.

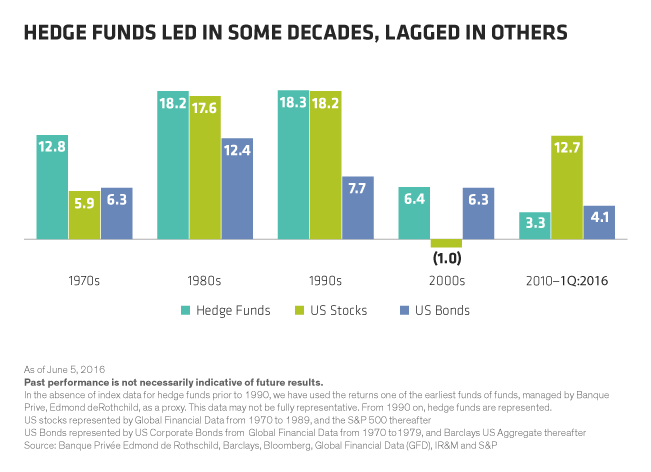

Yet the 1970s were a particularly strong period for hedge fund performance relative to US stock and bond indexes, as the Display below shows.

Pundits also called the end of hedge funds after the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998 roiled the hedge-fund market. Yet hedge funds outperformed stocks by a wide margin in the 2000s, as the Display also shows.

Nearly 50 years after the Fortune article, we’re hearing the same arguments reprised. While it’s true that hedge funds sailed into a perfect storm over the last 12 to 18 months, in our view the storm has passed. We think that those who follow the predictions of doom by redeeming their investments are likely to leave money on the table, just like investors who heeded the apocalyptic calls of the past.

After a period of poor performance, it’s important to remember why investors diversify across asset classes and investment strategies: Not all asset classes or strategies work at the same time. Diversifying among asset classes and strategies with different performance patterns tends to provide protection over the longer term.

And performance chasing—selling out of investments after a period of poor performance to reallocate into investments that have just had a good run—undermines the benefits of diversification and generally leads to poor results. Investors who bought the storyline behind a Business Week article, “The Death of Equities,” in August 1979, would have missed the great bull market for stocks that followed. The S&P 500 delivered annualized returns above 18% in the 1980s and 1990s, as the Display shows.

While it may be too early to declare that a hedge-fund recovery is underway, the last few months of performance have been encouraging. Hedge funds are generally seeing rebounds in oversold positions.

So what happened, and why do we feel better about the future? Let’s look at a few hedge-fund strategies.

Long/Short Equity

Long/short equity strategies buy (go long) stocks they find attractive, and sell (go short) stocks they find unattractive. For example, they might buy Ford and short Toyota, perhaps on expectations that Ford will gain market share from Toyota. They profit if Ford stock rises, or Toyota falls, or both, but are generally protected if the entire industry or the entire market collapses.

The first quarter of 2016 was a blood bath for many long/short equity funds. In the first half of the quarter, several huge hedge funds that are structured like bank proprietary-trading desks suffered large losses in the overall market decline. The firms’ stop-loss limits forced their traders to unwind their portfolios by selling their long positions and covering (buying back) their short positions.

As funds unwound their positions, the selling pressure hurt long positions while short covering (buying back shares that had been sold short) set off a rally in stocks that the funds had expected to do poorly. That put downward pressure on the relative returns of long-only active managers, as well as hedge funds.

We think these technical selling pressures have eased, and we’ve seen the beginnings of a performance rebound in long/short equity funds. Even after a modest recovery, many managers have told us they believe their portfolios are still trading at significant discounts to intrinsic value, suggesting the potential for further gains ahead.

Event-Driven Funds

Event-driven funds invest in stocks and bonds expected to increase in value as a result of corporate mergers, acquisitions, spin-offs, or other corporate actions that may or may not come to fruition. For example, merger-arbitrage strategies seek to profit from the discount, or spread, between the stock price of an acquisition target and the price offered by the bidder. The discount between the target’s stock price and the bid, which is captured by investors if the deal closes, reflects the perceived risk that the deal may collapse.

The last-minute collapse of a record volume of mergers and acquisitions hurt returns for many event-driven managers in 2015 and again in the first quarter of 2016. For example, aggressive enforcement of antitrust law put an end to the $6 billion merger of Office Depot and Staples. Similarly, a new US regulation aimed at stopping tax inversions caused Pfizer to walk away from its planned $150 billion merger with Allergan. (Tax inversions are mergers of US and foreign companies that result in the combined firm being domiciled outside the US, reducing the US entity’s tax bill.)

However, deal volume remains robust and deal spreads (the amount that could be earned if a proposed merger successfully closes) widened in response to the increased risk that mergers might be canceled or other event-driven strategies might fail. That is, the industry adjusted to the more aggressive regulatory environment. And when deals, such as the merger of Time Warner Cable and Charter Communications, went through in April and May, they were generally more profitable for merger arbitrageurs and other event-driven fund managers.

Distressed Debt

Distressed debt investors buy bonds or bank loans selling far below par value and at perceived discounts to fair value, as many financial institutions are forced to sell bonds that are downgraded. The selling pressure creates opportunity, because the bonds may rebound when the selling pressure subsides, the company’s business recovers, or the bonds are restructured through a negotiation with management, stockholders and other creditors.

Many distressed debt managers suffered from illiquidity during the high-yield bond market sell-off in 2015. Some are now bouncing back in the high-yield market recovery. In fact, the sell-off in distressed debt led many long-term investors to believe that there was significant value in the holdings of some funds that were hard in 2015.

Despite the doom and gloom reported by the media, investors did not redeem their investments in every hedge fund that suffered in the downturn. On the contrary, one distressed-debt fund that was among the hardest hit in 2015 recently closed a $400 million round of new investments from sophisticated investors expecting a rebound in the fund’s oversold positions.

Fee Arrangements Can Help

We think the recovery is underway and has a ways to go. Many hedge funds are still below their high-water marks, as they have not yet recouped the losses that they suffered through this difficult period. Until these funds reach their high-water marks, their existing investors will pay greatly reduced or no incentive fees, so they will capture a larger share of returns. Withdrawing from funds with such high water marks eliminates the fee benefit intended to help investors more quickly recoup their losses.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.