Global markets have taken heart from a truce in the trade war and signs of yet more monetary-policy stimulus. Easy money may well give a short-term lift to asset prices, but longer-term prospects look more challenging, especially for Europe.

We see two snags with the latest market narrative.

Uneasy Truce

First, the truce in the trade war is uneasy at best. If, as we believe, the trade war is just the beginning of a broader, multiyear conflict between the US and China, it probably won’t be long before things again take a turn for the worse. Plus, there’s the possibility that the trade war could spread to other countries—tariffs on European cars, anyone?

Debt Trap

Second, even though central banks are ready to provide more stimulus, we’re worried that policy effectiveness is starting to weaken. Surely, the answer to what ails the global economy cannot be even lower interest rates and more quantitative easing? And even if more stimulus does help stabilize growth, it’s likely to do so by encouraging individuals and companies to take on even more debt, driving interest-rate sensitivity higher and the equilibrium interest rate even lower. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has, rightly in our view, called this a debt trap.

Twin Vulnerabilities

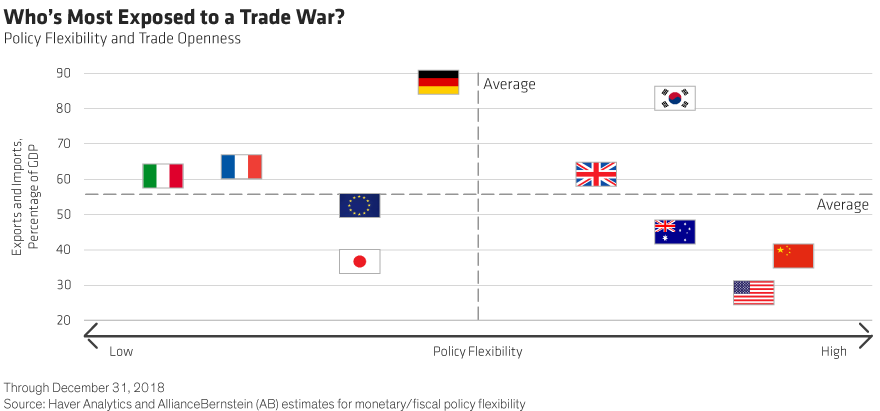

Faltering global growth presents a particular challenge for Europe. That’s not just because the euro-area countries are more reliant on international trade than the US and China, but also because they have far less policy flexibility. These twin vulnerabilities are highlighted in the display below: if downside risks to the global economy really do start to crystallize, the last place you would want to be is in the top left-hand corner, with a high sensitivity to international trade and low policy flexibility.

This lack of euro-area flexibility applies to both monetary and fiscal policy. The European Central Bank (ECB) has signalled its intention to inject fresh stimulus, but with interest rates negative and its balance sheet already bloated, it’s not clear what’s left in its monetary-policy toolbox; President Draghi’s recent pleas for more help from fiscal policy suggest that the ECB may share these concerns. Fiscal policy, meanwhile, is still hamstrung by the euro area’s budgetary rules, weak starting positions in many countries and Germany’s reluctance to use its own considerable fiscal space.

This lack of euro-area flexibility applies to both monetary and fiscal policy

This lack of euro-area flexibility applies to both monetary and fiscal policy

Emperor’s New Clothes

This is the tricky position that Christine Lagarde will inherit in November, when she succeeds Draghi as ECB president. We think Lagarde is a good choice: she has the stature and communication skills to do the job and is also likely to appreciate the broader political context in which the ECB operates. But she will assume her new role at a pivotal time.

We expect a significant easing of ECB monetary policy in September. That should be enough to stabilize the economy and reassure markets if, as we expect, the global slowdown remains shallow. But it’s unlikely to be enough to lift growth and inflation in the region. Nor will it be enough if the slowdown subsequently mutates into something less benign. In the latter case, markets would likely turn more skeptical, and see through the Emperor’s new clothes to reveal a disturbing lack of policy options.

Darren Williams is Director—Global Economic Research at AllianceBernstein

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time. AllianceBernstein Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.