The coronavirus crisis has exposed several potential weaknesses in modern business management. For decades, we’ve favored efficiency—possibly at the expense of robustness. Now, we may see that trend reverse, both in supply chains and capital allocation. But there’s one area where efficiency may prevail. As we emerge from this crisis, businesses may begin to favor increased automation over labor. Beyond increasing productivity, robots and computers aren’t at risk in a pandemic.

RE-OPTIMIZING SUPPLY CHAINS

Overly optimized supply chains represent a major risk recently unveiled in corporate business models. Efficiency has been the dominant theme for decades, prompting companies to develop lean, highly sophisticated global supply chains to maximize returns on capital. The downside? Production becomes susceptible to shocks. That fragility has been exposed. Consider early in the crisis, when European carmakers contended with the shutdown of a critical supplier’s main production center, near the heart of Italy’s coronavirus outbreak.

But the recently revealed cracks extend beyond the virus. Ongoing geopolitical and trade tensions, most notably between the US and China, have put even more pressure on global manufacturing. As a result, many companies were already repositioning their supply chains—moving production to Vietnam or other countries for exports, while building local Chinese production facilities to meet domestic Chinese demand. Those actions will likely continue in full force. Yet a new wrinkle may arise—essential industries maintaining production “back home.”

How this plays out in practice remains to be seen. It would be highly inefficient for every country, even long-time allies and strategic partners, to have redundant production facilities and personnel. Nevertheless, we expect some political pressure calling for a redesigned manufacturing footprint, especially in industries like pharmaceutical production. Should the movement toward nationalized supply chains gain traction, we would likely see a reversal in some of the pro-growth and disinflationary pressures which have benefited the global economy in recent decades.

As the world emerges from the pandemic, we also expect management teams to renew their focus on understanding their supply chains, sourcing from multiple vendors, and establishing inventory buffers of critical input materials. These actions would weigh on corporate margins and returns on capital in the medium term, but businesses who undertake them should be poised for longer-term success.

ROBUST CAPITAL ALLOCATION

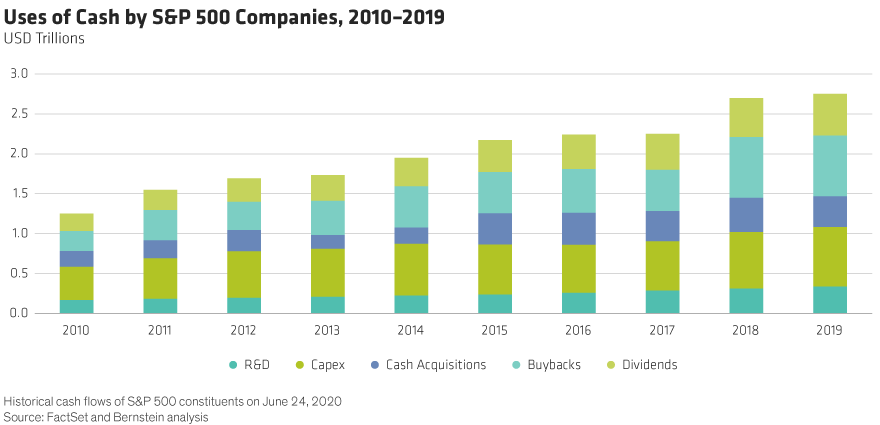

Optimized supply chains aren’t the only business practice under scrutiny. Balance sheet management has also been driven by efficiency. Historically, corporate executives have avoided sitting on excess cash, and have even been forced at times by activist investors to return it to shareholders. In fact, distributing capital to investors comprises a key element of a dynamic and thriving economy—it allows cash to be deployed for economic growth rather than idly accumulating in a bank account. Now, however, many companies have been forced to take emergency measures to conserve cash to ensure their future viability.

In some cases, that’s unavoidable. If you run a restaurant whose sales plummet to nearly zero, there’s little you can do to avoid a major hit. But if your restaurant already carried substantial debt, your stockholders’ investments may not have survived even a typical recession.

For companies with conservative financial positions, downturns like the current one present an opportunity to deploy cash at higher rates of return by cheaply acquiring competitors or assets. In some ways, balance sheet management allows them to benefit from chaos, which the author and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb has referred to as being “antifragile.”

As companies emerge from this crisis, some may decide that their prior levels of efficiency seem worth the risk. But for those looking to mitigate fragility and improve operational and financial robustness, we expect lower medium-term returns on capital, along with a higher probability of surviving and thriving in future downturns.

Listening to corporate executives across a range of industries, however, we remain cautious. We don’t expect capital allocation and balance sheet management for large companies to change too much. Thanks to the widespread liquidity in financial markets, many companies have been able to draw on existing credit lines or issue more debt to ensure their survival. Some are now opportunistically looking to take advantage of the crisis, while others remain in a defensive crouch. Looking forward, we’re not hearing senior executives discuss establishing more conservative balance sheets or reducing the amount of cash returned to investors; in fact, most have reiterated their commitment to prior targets.

AUTOMATION AND THE BALANCE OF LABOR AND CAPITAL

Though companies may leave capital allocation practices intact, we may see them pivot in other ways, such as doubling down on automation. Recessions have historically served as catalysts to replace labor with capital. Though higher unemployment rates pressure wages, falling revenues frequently overwhelm that effect. This incentivizes companies to invest in labor-saving technology and hire more-skilled workers as they emerge from the downturn.

This time is likely no different. As companies look at their exposure to the pandemic, they may conclude that robots and software—which can’t get sick—could have improved their performance.

Which companies stand to benefit most directly from a trend toward automation? Those providing the underlying technologies—including industrial equipment makers, semiconductor companies producing chips, and those delivering the networking infrastructure and bandwidth that form the backbone of “smart” factories. In addition, companies which can automate without having their lower-cost profile priced away by competitors should see their margins improve.

At the same time, any acceleration in automation will continue to exacerbate the tensions between capital and labor, which could have unpredictable macroeconomic and societal consequences. The Brookings Institution has flagged 36 million jobs (out of a pre-pandemic 150 million) in the US that remain highly susceptible to automation and could now be at increased risk. Not only would an acceleration have a major effect on corporate profitability, it would also have political and macroeconomic ramifications for the most vulnerable socioeconomic groups and geographic areas.

HARDER, BETTER, FASTER, STRONGER?

As we look across the corporate landscape, especially in the US, increased automation that exceeds current expectations seems likeliest. That should continue to fuel corporate returns—and the widening rift between providers of labor and providers of capital.

Much of the supply chain repositioning was already unfolding due to the ongoing backlash against globalization, recent trade tensions, and changing labor market costs in different countries. Barring a major national security-inspired push, our discussions with management teams point towards increased robustness, but with relatively limited consequences for the economy and markets.

Finally, some market watchers have suggested companies will face headwinds returning capital to shareholders or financing their operations with debt in the future. And some companies may go that route to strategically improve their “antifragility.” But unless governments step in to bail out industries and regulate their shareholder returns once the economy recovers, corporate managers seem inclined to allocate capital after the pandemic in much the same way as they did before.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.