Following pure valuation metrics today could leave equity portfolios with severe imbalances—especially in financials. But by studying patterns of the past, investors can gain insight into investing in underappreciated stocks by applying a human touch.

For decades, investors have assessed stock valuations with a few key metrics. These include the price/book ratio (P/B), which compares a company’s share price to the value of its assets in order to judge the potential based on a normal return on the company’s assets. The price/earnings (P/E) ratio—another favorite—expresses whether the market believes that a company’s near-term or long-term earnings are valued fairly by its share price.

Passive Portfolios Risk Imbalances

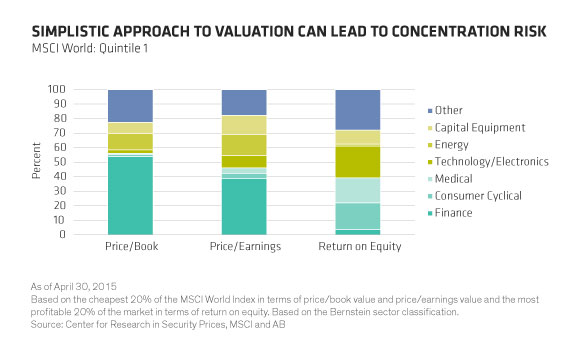

Today, it’s become fashionable to invest in attractively valued stocks using passive strategies. But what would a portfolio of cheap stocks look like if it were based strictly on these indicators?

It would probably look lopsided. If we simply took the cheapest 20% of global stocks according to P/B or P/E, we would end up with a portfolio that had more than half of its weight in just two sectors: financials and energy (Display). This portfolio would also be very light on all other sectors, including technology, where companies are highly profitable and often more expensive. It wouldn’t be able to capture the attractive valuations that can be found in the tech companies that stand out from the crowd.

Some of these distortions can be mitigated with a style index or a smart-beta approach. However, these too are prone to imbalances. For example, more than 30% of the MSCI World Value Index was in financials at the end of April—much higher than a standard cap-weighted index. And if you were to strip out financials entirely, an investor would forgo an opportunity to profit from a rebound of cheap financial stocks that are on the road to recovery.

Regional valuations are also tricky. While US equities look expensive according to P/B and P/E ratios, we’re still finding many attractively valued stocks across the market and in different sectors. And although Japanese and emerging-market stocks look cheap from a global perspective, we’d be wary of blindly allocating to either set of candidates on a regional basis without careful vetting.

Case Study: The Commodities Supercycle

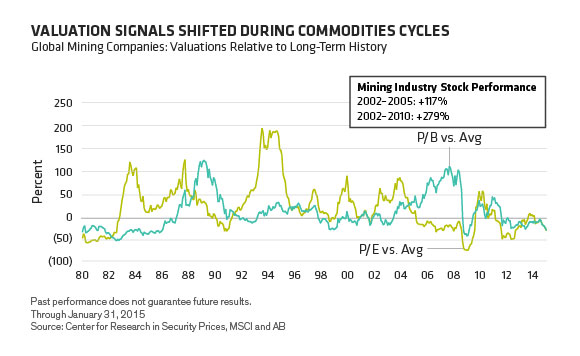

History shows that valuation metrics require context to be effective. Take the commodities supercycle as an example. In the early 2000s, as an oversupply of commodities swept world markets, prices of metals like copper and iron ore hit lows. As a result, shares of mining companies were depressed. P/B multiples were very low relative to their history because investors didn’t believe the sector would recover, yet P/Es were initially quite high because many companies weren’t profitable at the time (Display).

Yet from 2002 to 2005, the mining industry staged a sharp recovery. At that time, China had just joined the World Trade Organization and launched land reforms that triggered a vast domestic building reconstruction boom in the world’s most populous nation. China’s insatiable appetite for commodities benefited Russia and Brazil. Mining companies were the big winners.

At that point, P/B ratios of mining companies began to increase, peaking in 2007 at more than double their long-term average, while P/E values fell. Lower P/E values reflected growing concern among investors that the commodities supercycle, as it would later become known, couldn’t really last too long. In fact, it lasted through 2010, much longer than anyone thought at the time.

Ask the Right Questions

In this example, a simple index approach wouldn’t have worked. In the mining sector, P/B and P/E often offered conflicting signals, and looking at the average of the two would have been inconclusive. Only by understanding the dynamics of different valuation metrics—and applying them with fundamental research to industry and company developments—could an investor have derived the knowledge needed to generate outperformance from the changing stages of the commodity supercycle.

That’s why fundamental research is so important. When a company is trading at a cheap valuation, an investor needs to answer underlying questions about why the stock price is low. These questions can’t be answered by even the most sophisticated computer, metric or algorithm. Discipline, human judgment and a thoughtful evaluation of a wide variety of issues are essential ingredients for developing high conviction in the return potential of cheap stocks.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations, and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indices or any securities or financial products. This report is not approved, reviewed or produced by MSCI.