There are other plausible explanations. Investors may think that the government won’t last long—or that it will act very differently once it gets to sit at the high table (think Greece’s Syriza). The market probably also draws some comfort from the recently toned-down anti-euro rhetoric of both M5S and the League.

Collision Course with Brussels and Creditor Nations?

But there’s also a clear element of complacency at play in the market’s modest reaction.

There are considerable differences between the electoral platforms of M5S and the League, but the parts they can agree on—repealing the 2011 pension reform, tax cuts, minimum incomes and higher spending—are likely to put Italy on a collision course with Brussels and the euro area’s creditor nations. And recent comments from both parties suggest they are happy to precipitate a confrontation.

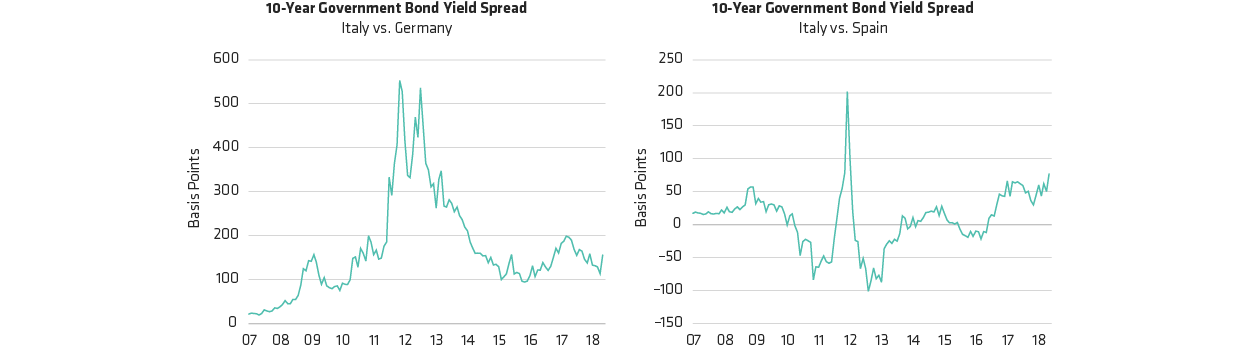

If a new government pursues these policies in earnest, it will also put the ECB in a tough spot. Quantitative easing has provided support for peripheral bond markets, but the turning point in the sovereign-debt crisis was ECB President Mario Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech in mid-2012.

That speech was ultimately the result of a grand bargain—Italian President Silvio Berlusconi resigned (November 2011), the fiscal compact was signed (March 2012), Draghi delivered the speech (July 2012) and German Chancellor Angela Merkel supported the ECB president despite the Deutsche Bundesbank’s protests.

If a populist Italian government does decide to openly flout the euro area’s budget rules, we’ll end up with a classic fiscal free-rider problem (think Greece pre-2010 or an International Monetary Fund program with no conditions). There are likely to be limits to the ECB’s and/or German government’s tolerance for such a situation, particularly given the example it would set for other countries.

More Downside than Upside Risk

So, what are the market implications? It’s certainly possible that the consensus view is right and that the bark of a M5S-League coalition will be worse than its bite—or that the coalition will be so short-lived that it will have little impact.

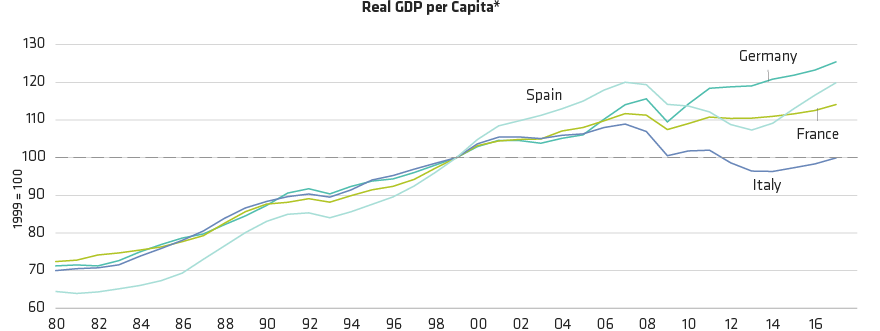

But we struggle to find the positive news that could drive Italy’s bond-yield spreads lower from this point. And we can see that a scenario recently considered a tail risk—a populist Italian government, flouting Europe’s fiscal rules and in conflict with its creditor nations—seems to be playing out before our eyes. And we keep going back to Italy’s woeful GDP per capita charts.

Sooner or later, it seems that something has to give.