With each passing month, more questions are being asked about the sluggish US economic recovery. Why has growth been subdued since the recession ended in mid-2009? What's changed in the economy? How long can loose monetary policies persist before promoting more inflation or creating a new bubble?

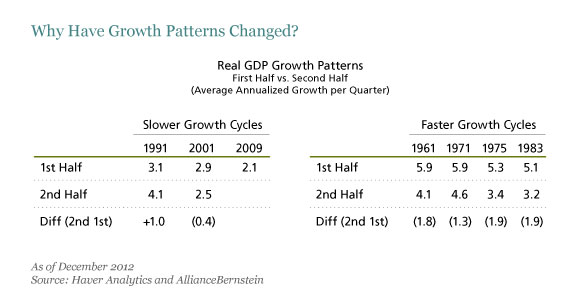

To answer these questions, you first need to understand what is driving the US business cycle. In the initial stages of the last three US economic recoveries (1991, 2001 and 2009), the pace of growth was roughly half as fast as during recoveries from the 1960s to the 1980s (Display). In the past, it was widely believed that deep recessions were followed by sharp recoveries, while mild, short downturns were followed by weaker rebounds.

That argument doesn't hold water anymore. After the worst economic slump since the Great Depression in 2008-09, we've seen nothing but slow growth.

Part of this pattern has been created by a change in the underlying causes of recessions. The past three US downturns were driven by financial imbalances and sharp declines in asset prices. This triggered spending and investment corrections as well as a crisis in the capital markets and banking system.

But from the 1960s to the 1980s, US recessions were largely caused by imbalances from accelerating inflation of both consumer and producer prices and the subsequent tightening of monetary policy. It's much harder for an economy to extract itself from financial imbalances than from real sector imbalances.

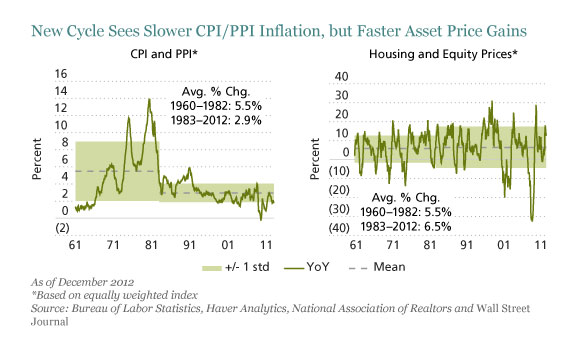

Price patterns have also changed dramatically. During the 1960s, 1970s and the early 1980s, the consumer price index (CPI) and producer price index (PPI) rose rapidly (Display), matching the average annual increase in asset prices like real estate and equities. But since the early 1980s, the CPI and PPI rose only half as fast as in the earlier periods, while asset prices rose much faster.

These changes are extremely important. Wage trends have an affinity with CPI, while business profits are correlated with producer prices. So in good times, rising wages and business prices—and expectations that current trends will continue—encourage people and businesses to take on more debt, thereby supporting additional spending and investment.

Yet, during growth periods in the past two decades, leverage has shifted from income flows to balance sheets as asset prices fueled individual and corporate wealth. In the equity market boom of the late 1990s, many companies used their share price as a currency to invest and expand. Similarly, in the cycle that started in 2001, rising house prices allowed individuals to borrow more for additional real estate investments and to increase spending.

This shift creates the potential for more economic instability—especially since asset prices have become demonstrably more volatile over time. And since the Fed focuses primarily on consumer prices, changes to asset prices and wealth are more likely to become the “accelerator” of economic growth by driving increased use of credit and investment.

In our view, a successful monetary policy must ensure that wealth gains from rising asset prices are durable and linked to fundamental changes in the real economy—not just a temporary benefit from artificial and unsustainable liquidity flows. We don’t think that the Fed can achieve this by focusing only on the core inflation rate and the unemployment rate, which do not capture the fundamental shifts that drive the economy. Without changing the framework that underpins monetary policy, the Fed won’t be able to address the challenge posed by rising asset prices to US economic growth.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AllianceBernstein portfolio-management teams.