Passive investments continue to gain popularity, generate record flows and grab headlines. We understand the appeal. But investors must also consider some of the risks of tethering their fortunes to a benchmark.

This week, the active-passive debate was in the spotlight again. The Wall Street Journal reported that active US equity managers had done well so far in 2015, with many beating their benchmarks. Yet data from eVestment showed that passive global institutional flows outpaced active by a margin of $1.6 trillion from June 2007 to the end of 2014, according to FundFire.

Passive Pros and Cons

For active managers, these numbers are an ongoing headwind. Investing firms today can’t deny that many clients don’t want to hold actively managed portfolios anymore. At the same time, it’s important to explain to clients the pros and cons of investment options; our view is that a combination of passive and active would be appropriate for many investors. And often the appealing features of passive portfolios can obscure the hidden risks.

Many investors today opt for the simplicity of buying low-cost exchange-traded funds that mimic a benchmark. On the surface, a passive portfolio might seem impassive in that it wouldn’t be subject to the behavioral biases that may influence active managers, who are constantly digesting new and changing information.

The lower governance costs of passive solutions are another attraction. Investment advisors don’t have to spend time explaining why manager performance is different from that of the benchmark, or making hiring and firing decisions. But this focus can sometimes substitute one risk for another, because passive solutions are prone to concentration and valuation risks.

Watch Your Weight

For example, today, ExxonMobil’s weight in the S&P 500 is about 10 times the average stock in the index. While the company is a powerhouse in the energy sector, is it really 10 times more attractive than so many stocks to deserve such a large allocation?

Similarly, when a stock or sector becomes pricey, a benchmark will continue to hold it at an even higher weight than when it was more reasonably valued. For example, even after the decline in high-momentum stocks in 2014, many Internet and biotech names weren’t cheap. An active manager can think twice about owning a stock trading at an exponential multiple of its future earnings.

Benchmarks and Bubbles

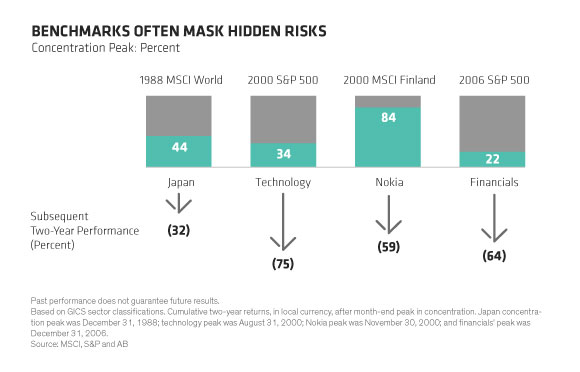

Bubbles are another problem. In 1988, Japanese stocks reached 44% of the MSCI World Index—over five times more than today and a bigger weight than US stocks had at the time. During the next two years, Japanese stocks dropped by 32%. At the peak of the Internet craze in 2000, the technology sector ballooned to 34% of the S&P 500, while Nokia accounted for 84% of Finland’s benchmark. And in 2006, an investor in the S&P 500 would have had a heavy allocation to financial stocks. Each of these exposures was followed by two years of devastating performance.

Active investors should always be on the lookout for the next market bubble—and you never know where one might pop up. These examples show how investors who opt for an index in an effort to manage relative risk may not be aware of the absolute risk inherent in buying a benchmark. In other words, if the market collapses, an allocation to the benchmark won’t protect you.

Of course, passive portfolios can be used as a cost-efficient way to capture market returns. But in our view, allocations that include both passive equities and high-conviction active portfolios can create a powerful combination of beta and alpha to help investors meet their objectives.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.