How was this possible? Aren’t bonds highly sensitive to interest-rate movements? Yes, but as long as they don’t default, bonds also produce a steady stream of income. And when rates rise, investors can reinvest the proceeds of their maturing bonds in newer—and higher-yielding—bonds. This often outweighs any short-term losses from rising rates and increases total return.

In other words, investors who rely on their bond portfolios to provide income over a long time period should be rooting for higher rates.

A rapid—and unexpected—rise in rates can be harder for investors to navigate. In 1994, inflation worries prompted the Fed to lift rates at a much faster clip over a shorter period of time—and without advance notice. The 10-year US Treasury Index lost nearly 4% during that cycle.

US high yield, however, was up 1.4%—evidence that active bond managers can still deliver positive returns even when Treasury prices fall, by using insights on valuation and credit quality to choose bonds that can withstand broader market downturns.

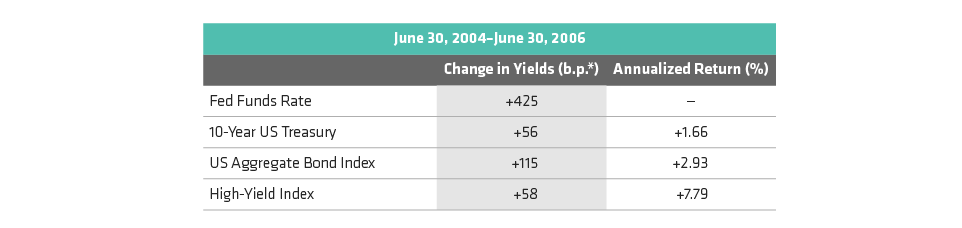

Today’s conditions more closely resemble those in 2004: the economy is gaining traction at a measured pace, inflation remains under control, and policymakers have tried to avoid surprises by clearly telegraphing their plans to financial markets. Under such conditions, bonds tend to do well.

How to Position Your Portfolio

So how should investors prepare? Those with high-income strategies can diversify their interest-rate and economic risk by taking a global, multi-sector approach. This could involve adding sectors such as US securitized assets, which benefit from strong credit fundamentals and consumer spending.

Such an approach might also involve a higher allocation to emerging markets, which stand to gain from stronger US and global growth. We see opportunities in some attractively valued local currency–denominated bonds from countries that are cleaning up their public finances and bringing inflation under control.

US high yield is in the later stages of the credit cycle. That means investors should be choosy about what they buy. But they shouldn’t avoid this market altogether. High-yield bonds are less sensitive to interest rates than other bonds are. And their steady income can enhance total portfolio returns even as rates rise.

Investors who want to maintain a lower risk profile might want to consider a barbell strategy that mixes interest-rate and credit risk and adjusts the balance as conditions and valuations change.

Even as rates rise, this approach would involve US Treasuries and other government bonds, which provide important diversification to credit exposure in all environments. Over the medium term, more than 90% of US Treasury returns come from the yield. That means that rising rates can dramatically boost income for investors who are not primarily focused on short-term price fluctuations.

Bonds are a critical source of income and a useful diversifier of riskier equities. Rising interest rates may cause some short-term volatility, but investors with a multi-year investment horizon are likely to benefit over time as rates rise.