Bond strategies that balance interest-rate and credit risk struggled in 2018. Is this time-tested approach past its prime? Hardly. We think investors will need to blend exposure to both to generate income and limit risk in 2019.

Pairing high-yield corporate bonds and other credit assets with high-quality government debt in a single strategy has historically been a good way to manage volatility and limit downside risk. That’s because these bonds usually take turns outperforming each other.

For example, faster growth tends to feed inflation and push up interest rates, which erodes the purchasing power—and market value—of government bonds. But growth boosts consumer spending and corporate profits—provided inflation doesn’t get out of hand. That’s good for high-yield bonds because it lowers the odds of default.

When growth slows, it’s the risk-reducing government bonds that outperform and help compensate for losses in more growth-sensitive credit assets. A portfolio that combines both in an integrated way can thrive in most market and economic environments.

2018: An Unusually Challenging Year

Sometimes, though, returns for both groups of assets move in the same direction. That’s what happened at times during 2018, as anyone who reviewed her investment statements will have noticed.

A quick recap: In the first half of the year, the Federal Reserve pushed up interest rates amid signs of strong US growth while simultaneously shrinking its balance sheet. And by year-end, the European Central Bank stopped expanding its own balance sheet and the Bank of Japan’s net asset purchases slowed to a crawl. This hit the prices of many interest-rate-sensitive bonds, driving the US 10-year Treasury yield in October to a seven-year high near 3.25%.

Then, as tighter financial conditions started to bite—especially outside the US—and trade tensions worsened, high-yield bonds and other credit assets sold off, reducing returns on the return-seeking side of balanced bond strategies.

The result: both sides of balanced income strategies underperformed. But 2018 was unusual because it was a transition year: markets were moving away from a prolonged period of easy money and low volatility to one of slower growth, tighter financial conditions and higher political risks.

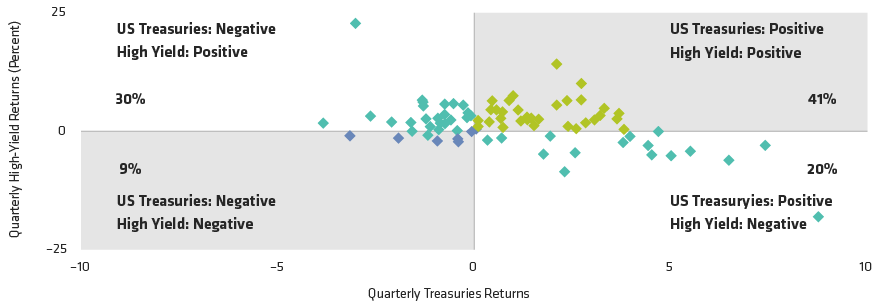

The good news is that periods of correlated performance among credit and government bonds are rare and usually don’t last long. While both types of assets struggled at times last year, it was only during the first quarter that both posted negative returns. And over the last 20 years, the two staged correlated sell-offs only 9% of the time. In fact, returns have risen together far more often than they’ve fallen—thanks, largely, to the income bonds produce (Display).