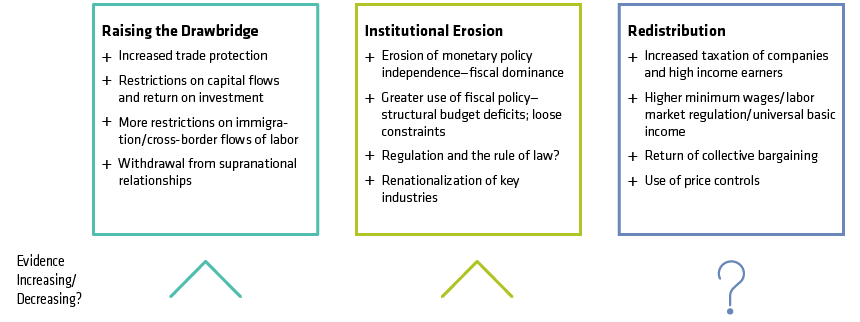

1) Raising the drawbridge. We’ve seen plenty of evidence of advances in this channel, with policies becoming more national and less global. There’s been trade conflict between the US and its partners, including China, Canada and Mexico. We’ve seen withdrawals from multinational arrangements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Agreement. Brexit and anti-Brussels sentiment fit the mold, too.

2) Institutional erosion. There have been many examples of efforts to undermine or ignore mainstream institutions. In the last couple of years, these included attacks on media independence, from complaints about “fake news” to the closing or limiting of media outlets in Hungary and Turkey. Fiscal policy constraints are being ignored, too—notably in the US, but also in Europe, by way of Italy’s budget proposals.

The days of independent central banks show some signs of being numbered, from criticism of the US Fed to Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s statement that his patience on central bank policy “has limits.” The dispute between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and former governor Urjit Patel—leading ultimately to Patel’s resignation—over the Reserve Bank of India’s independence is yet another example.

3) Redistribution. From the standpoint of income redistribution, the evidence of policy action has been scarcer. National income has been shifting away from labor for some time in industrialized countries, but this trend has largely flown under the radar so far. Globalization, technological disruption and institutional change have squeezed living standards for workers at the middle to bottom end of income distribution while bolstering corporate profits.

But the corporate sector hasn’t been a lightning rod for populist anger to this point. We’ve seen some efforts to raise minimum wages—South Korean president Moon Jae-in’s minimum-wage hikes of 16% in 2018 and 10% in 2019, for example. But we haven’t seen broader efforts to shift the balance of bargaining power from capital back toward labor—at least not yet.

But corporations might be next on the agenda. This could mean rethinking antitrust policies, addressing the notion that competitive dominance also means political power and more influence on public policy. Efforts to shift power back toward labor could find their way into policymakers’ hands. The UK Labour Party’s manifesto outlines some of the possibilities, including shorter workweeks, mandatory employee presence on boards and a bigger role for unions in collective bargaining.

Assessing the Big-Picture Impact

The populist surge is already shifting the global macroeconomic outlook. For some time, we’ve been emphasizing the ramifications of these policies in influencing the medium-term inflation path, but there are near-term consequences, too.

For example, the Trump administration’s fiscal-spending boost is putting upward pressure on US interest rates. The ongoing US-China trade dispute is muddying China’s growth prospects. Tangled Brexit negotiations and uncertainty about Italy’s politics cast a shadow on Europe’s economic outlook.

The bottom line, in our view, is that we shouldn’t expect a return to the policymaking orthodoxy of the decades that led up to the global financial crisis. We’re likely to see more populist-inspired initiatives through the three main channels.

Together, these policies are likely to shift potential macro outcomes in a more challenging direction. Even if nominal income growth were to stay the same, the mix would surely change, and we would see higher inflation, lower economic growth rates and more pressure on corporate profit margins.